Towards the 80th anniversary of the defeat of fascism, last steps of the Soviet military campaign.

Towards the 80th anniversary of the defeat of fascism, last steps of the Soviet military campaign.

In the previous installment we had left off in the final days of January 1945 when the vanguard of Soviet troops forced their way across the Oder River, which marks the state border between Poland and Germany, occupying a bridgehead 490 km west of Warsaw and just under 100 km from Berlin.

Upon crossing the Oder River, the Red Army occupied the city of Kienitz, the first city captured by Soviet forces on German soil. The Nazi troops were completely surprised. Upon entering the city, the Soviet soldiers found Germans strolling peacefully, restaurants filled with Wehrmacht soldiers, and trains running smoothly.

After recovering from their shock, on February 2, the Germans launched a major offensive to try to dislodge the Soviet detachment from the captured bridgehead west of the Oder. It was unsuccessful, although during the course of the battle a highly dangerous situation arose due to the intrusion of Nazi tanks into Soviet artillery firing positions. The heroism of the soldiers and officers prevented the enemy from achieving success.

As the days passed, the bridgehead expanded with the arrival of new detachments, but at the same time, there were constant German attempts to dislodge them from the conquered terrain. The fighting lasted for several days, with mixed results: both forces advanced and retreated. However, in the end, the Soviet troops prevailed, and the bridgehead was expanded, creating the conditions for the 1st Byelorussian Front, consolidated on the ground, to begin preparing the operations that would lead the Red Army to the capture of Berlin.

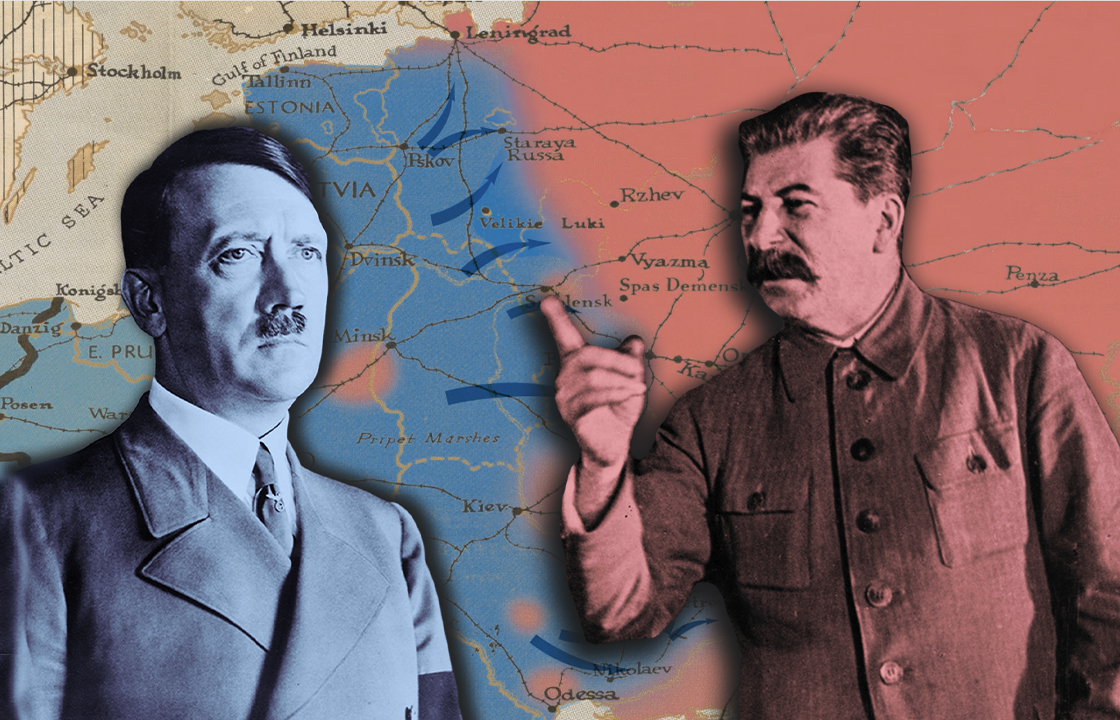

But the threat of a German counteroffensive was latent. Information reaching Moscow, sent from a wide variety of sources, was abundant. The Soviet command had to act with skill and comprehensive vision to move and concentrate troops in the areas where the enemy attack was anticipated. Furthermore, coordination at the highest level was necessary; the advance of the different fronts had to be coordinated and orderly. This task fell to the Grand General Headquarters (GHQ), from where Stalin directed the war. If one front advanced faster than another, there was a risk of creating gaps through which the enemy could penetrate and advance deeper, jeopardizing the offensive.

Understanding the situation, on February 24, the GCG brought the 19th Army, which was part of its reserve, into combat, allowing the offensive to regain the necessary momentum. On March 1, the 1st Belorussian Front went on the attack, and a few days later, the 2nd Belorussian Front. These forces reached the Baltic Sea coast, threatening the enemy from the northeast.

In this situation, the Soviet high command debated the best way to design the attack on Berlin, but there was no single idea. Although it was known that the Germans no longer had large shock forces or a continuous defensive line, it was also known that Hitler had withdrawn nine to ten divisions from the Western Front, which were being transferred to the Eastern Front with the intention of using them to defend Berlin. It was clear that the American-British troops were not the Nazis’ main enemy, and they even reserved the possibility of negotiating with them to contain the Soviet Union.

At one point, the Soviet high command believed that the final battle could be fought as early as February, but the troop preparation and the necessary combat and logistical security to wage the decisive battle had not been achieved.

The accelerated pace of the offensive over the past few months had stretched the logistics front line too thin. The necessary ammunition, supplies, and fuel for a battle of the magnitude planned had not been delivered. Likewise, the air force had not been able to approach, and new airfields had not been built on the ground soaked by the winter. The objective, “Berlin,” had to wait a little longer.

The information obtained by Soviet intelligence proved to be correct. The Germans were preparing for a strong counterattack that would break the Soviet line of attack: Hitler’s plan was to attack from Eastern Pomerania, located in northeastern Germany on the Baltic Sea. However, the timely intelligence obtained allowed for measures to be taken to counter the enemy’s attempt. The decision to halt the offensive was correct. The memoirs written by several German generals at the end of the war attest to this.

In this situation, the GCG decided to introduce new reserves into combat to prevent a likely German counteroffensive from Pomerania. At the time, this was the main German threat, and all efforts had to be focused on it. At the same time, the Nazis offered strong resistance, preventing the Soviet army from maintaining the accelerated pace the offensive had acquired in the preceding months.

However, within a few weeks, the 2nd and 1st Byelorussian Fronts completed the annihilation of the enemy group, and by the end of March, Eastern Pomerania was under Soviet control. Thus, the conditions were created for the Vistula-Oder Operation (two major European rivers, the first in Poland and the second in Germany). At the end of this, with the Soviet victory, almost all of Poland was liberated and the bulk of the fighting shifted definitively to German territory. In this operation, 60 German divisions were defeated, forcing the Hitlerite high command to transfer more than 29 divisions and four brigades from other sectors of the Soviet-German front and from Italy to try to guarantee the defense of Berlin.

The Vistula-Oder Operation marked a new level of combat capability for the Red Army, which advanced at an average pace of 25-30 km per day, while the armored armies advanced at 45 and even 70 km per day. They bore the brunt of the fighting. This operation was also characterized once again by an extraordinary display of disinformation actions that made it possible to conceal from the Germans the scope, timing, and main direction of the offensive.

On other fronts, combat actions also proceeded with great impetuosity. In Hungary, faced with the Soviet advance that had managed to cross the Danube River, the Nazis attempted a counteroffensive to drive them back across the river. They sought to save a large group of troops surrounded in Budapest, but they failed to achieve their objective. The Soviet army repelled all German attempts, and in mid-March (exactly 80 years ago) they prepared the conditions for an offensive to liberate Vienna, the Austrian capital. This operation began on March 16 and culminated on April 15 with the liberation of Hungary, part of Czechoslovakia, and Austria (including its capital). Germany lost its fuel supplies in Hungary and Austria and a significant number of its arms factories.

Thus, Soviet troops approached Berlin from two directions, north and south. Similarly, on Germany’s western front, American-British troops forced their way across the Rhine River, forcing the Nazi forces in that sector to surrender on April 17. In American historiography, this day is considered the date of the Nazi defeat. But the truth is that Hitler was still alive, and the fighting continued.

After postponing their breakthrough into Europe for years, maintaining an extremely careful pace of operations, the American command had now accelerated. Anglo-Saxon governments were pressuring their military commanders to hasten the attack in order to seize Berlin before the Soviets arrived.

On April 1, Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, wrote to Franklin Roosevelt, President of the United States. He said: “The Russian armies will undoubtedly seize all of Austria and enter Vienna. If they also take Berlin, will this not create in them the exaggerated notion that they have made the greatest contribution to our common victory, and will this not lead them to such a state of mind as to cause serious and very sensitive difficulties in the future? Therefore, I believe that from the political point of view we must advance as far east as we can in Germany, and should Berlin come within our reach, we must undoubtedly take it…” No further comment is needed.

In the interim between these battles, the Yalta Conference took place between February 4 and 11, attended by the top leaders of the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom. This meeting not only finalized details for the final defeat of Germany, but also discussed the future of Europe and Germany’s administration after the conflict, and designed the structure of the international system that would prevail in the future.

At the conference, the Soviet leader insisted to his counterparts on the need for his troops to adopt a more consistent offensive rhythm, at the same level as the Soviets were maintaining. Although several agreements were signed on this matter, it wasn’t until April that the Western powers appeared to act. Churchill’s letter to Roosevelt of April 1 is a clear example of this.

As if what is happening today in the Ukrainian conflict were a copy of the past, Stalin understood Roosevelt better than Churchill. The British Prime Minister was particularly concerned about what would happen in Poland and the future design of its borders. Furthermore, he advocated the idea of installing in power a Polish leader who had been sheltered in London throughout the war and who was nothing more than a pawn without any judgment of his own, at the service of the British.

In early March, a meeting was held in Moscow attended by several members of the State Defense Committee, chaired by Stalin. Among those present were Prime Minister Georgy Malenkov, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, Chief of the General Staff Aleksei Antonov, and Marshal Georgy Zhukov, commander of the 1st Byelorussian Front, who would have the primary mission in the attack on Berlin.

Antonov and Zhukov presented a report with specific proposals for the development of the operation. The idea was to attack Berlin from three directions: east, south, and north. Stalin approved it and ordered the fronts to be given the necessary instructions to carry out their respective missions. Thus, the operation against Berlin was authorized, pending execution. The date was March 9, 1945.

Leave a Reply