The Tuareg are an ancient Berber tribe settled throughout the Saharan regions of Libya, Algeria, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. The Tuareg are believed to have migrated from modern-day Libya in the 7th century AD under pressure from Arab invaders. As nomadic pastoralists, traders and farmers, they had some resistance to recurring droughts. Due to their nomadic lifestyle, the Tuareg never had a centralized leadership, but instead operated in kels, a kind of loose political confederation, and resisted any government systems.

The Tuaregs resisted the French military after their arrival in Africa in 1880, but succumbed to French power in 1898. The French taxed their trade, confiscated camels for military use, and attempted to end the Tuareg nomadic lifestyle. Political repression and economic difficulties caused by drought led to a Tuareg revolt in 1916–1917. Many significant events of the uprising took place on the territory of modern Libya.

The leadership of the Senussi order in Fezzan (the territory of modern Libya) declared jihad against the French colonialists in October 1914. Tagama, sultan of Agadez (present-day Niger territory), convinced the French military that the Tuaregs remained loyal to them, and through his intrigue, Senussi forces were able to besiege the French garrison in the sultanate on December 17, 1916. Tuareg rebels, numbering more than 1,000 people and armed with rifles and one cannon, defeated several French light columns. They captured all the major cities of Aïr and the area that makes up today’s northern Niger was under rebel control for three months.

On March 3, 1917, French forces liberated the Agadez garrison and began capturing towns controlled by the rebels. Subsequently, French authorities confiscated important grazing lands, used Tuaregs as forced conscripts and labor, and fragmented Tuareg societies by drawing arbitrary borders between Mali and its neighbors. The Tuaregs themselves did not recognize the arbitrary state borders drawn by the French, and always recognized themselves as a single, artificially divided people. Since then, part of the Tuaregs and other Berber peoples have lived in the historical region of Fezzan, which fell to Libya. According to various estimates, the Tuareg population in Libya ranges from 17,000 to 560,000 people.

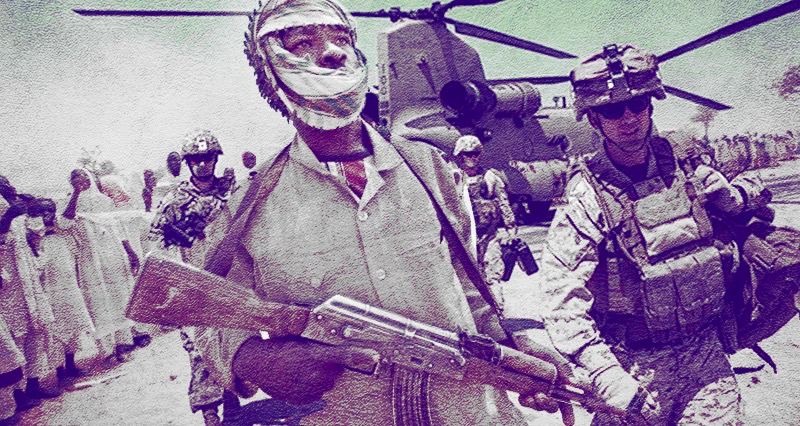

Tuaregs in Gaddafi’s army

In the 1980s, some Tuaregs fled Mali for Libya due to difficult conditions. At that time, Mali was going through a difficult period of drought and famine. Moussa Traoré’s government has squandered most of the international aid aimed at overcoming the crisis. The Traoré regime was hostile to the Tuareg communities and neglected their interests. In Libya, young Tuaregs were trained in the Libyan army and in training camps for Libyan guerrillas. These people were the main force that started the uprising in Mali in 1990, when Tuareg separatists attacked a government building in Gao. Repression by the Malian army led to a full-scale war. The conflict subsided when Alpha Oumar Konaré formed a new government in 1992 and began paying reparations.

In 1994, Libya supported a group of Tuareg rebels who again attacked Gao. In those years, the Tuaregs organized an armed uprising not only in Mali, but also in Niger. The situation was such that the governments of the countries where the Tuaregs migrated, for the most part, opposed them. The only exceptions were Libya and Algeria. In Mali and Niger, the Tuaregs could not find their new home and fled to Libya and Algeria, where they began to unite with militants, thereby forming rebel groups.

During the 2011 Libyan civil war, the Tuaregs sided with the Gaddafi regime, many of them serving in the regular Libyan army for more than 20 years. Gaddafi supported Tuareg refugees for many years, trained them in military skills and assured them that he wanted to help the Tuaregs regain their lands, although he did very little to make this actually happen. Instead, he sent them to fight in Chad and Lebanon. It is known that in 2009, the Libyan government granted citizenship to 1,722 Malian Tuareg fighters and 83 officers who were supposed to serve in a special battalion appointment under the command of Tuareg General Ali Kanna.

Ali Kanna’s southern forces in Sebha were almost the only stronghold of the Gaddafi regime after the fall of Tripoli on August 28, 2011, which were still controlled by the Jamahiriya. On September 6, 2011, a large convoy of pro-Gaddafi Tuaregs from the southern Cannes battalion crossed the Algerian border to then seek refuge in Niger. According to rumors, Kanna was part of this convoy, and Gaddafi himself and his son Saif al-Islam were supposed to join Kanna on the way to Burkina Faso. Ali Kanna, unlike Gaddafi, managed to escape. In 2013, he returned to Libya from Niger. Later he would play a role in Tuaregs life in Libya.

Unlike the Tuaregs, other Berber peoples of Libya fought against Gaddafi. In 2011, there were approximately 600,000 Berbers living in Libya. In the north, Berbers live around the city of Zuwara (named after the Berber tribe) and in the Nafusa mountains. A distinctive feature of this part of the Libyan Amazigh community is its adherence to Ibadism, a branch of Islam historically associated with the Kharijite movement. During the reign of Muammar Gaddafi, the Berber-Ibadi identity was suppressed in favor of an Arab identity. The local population took an active part in the 2011 uprising against the Libyan Jamahiriya and consequently achieved a certain autonomy.

Libyan Tuaregs after the fall of Gaddafi’s regime

After the fall of the Jamahiriya in 2011, many Tuaregs continued to remain “loyal” to the Gaddafi regime, which led to repression against them by the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA). The Tuaregs who returned to northern Mali created The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). The Tuaregs call the territory of their settlement between several states in northern Africa in honor of the ancient dry river. Former Libyan consul in Mali, Tuareg Mousa Kuni, tried to negotiate with the new Libyan authorities on the inclusion of Tuaregs in the security forces of post-Gaddafi Libya, but unsuccessfully.

In 2013, Ali Kanna, returning from Niger, began to gather an army of Gaddafi supporters from local Tuaregs and people from neighboring Mali, Niger and Chad. Having played the role of mediator in the Ubari conflict between the Tuareg and Toubou in 2015, he called to the creation of a multinational army of the south (Fezzan army), which supported the ideology of the Jamahiriya. At the same time, Ali Kanna opposed General Haftar’s Libyan National Army, where most of the officers of Gaddafi’s army served.

In October 2016, officers in control of the southern Fezzan region unilaterally appointed Kanna as their commander without consulting Khalifa Haftar. Following his appointment, Kanna stated that his forces would not participate in politics and called for the unification of Libya between the Government of National Accord based in Tripoli, and the House of Representatives, based in Tobruk. In May 2017, Kanna forces peacefully took control of the El Sharara oil field from the 13th Misrata Brigade. The Libyan Tuaregs controlled the illegal transportation of oil to neighboring African countries. Complex and contradictory relations link the Tuaregs of Fezzan with the Arabs and the Nilo-Saharan Toubou people, who live in southern Libya and the Republic of Chad.

In June of the same year, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi was rumored to have joined Kanna forces in Ubari after his release. In July, Kanna traveled to Algeria to meet with the Algerian Minister of Foreign Affairs Abdelkader Messahel. Tuareg forces in Cannes control the Ghat region bordering Algeria. Kanna allegedly has close ties to Algerian intelligence. In 2018, a new body was created that claimed to speak on behalf of the Tuaregs – the Supreme Tuareg Social Council headed by Moulay Gnedi. He, in turn, is closer to General Haftar’s Libyan National Army, an alliance with which the Tuaregs are skeptical about due to the fact that some Libyan Tuaregs are perceived in Tripoli and Tobruk as “foreigners.”

Strengthening of Islamists after 2011

The fall of the Libyan Jamahiriya not only aggravated the Tuareg issue, but also provoked the activation of al-Qaeda in northern Mali. On November 9, 2011, in a telephone interview with a private Mauritanian news agency, major AKM field commander Mokhtar Belmokhtar, whose militants terrorize the south of Algeria, often crossing the border of neighboring states, confirmed that he had received the first shipments of weapons from Libya. Al-Qaeda cells have predictably become more active in Algeria, Mali and Niger.

A new armed Islamist radical Tuareg movement Ansar al-Dine was formed in Mali , which was led by the Tuareg Ayad ag Ghali. He participated in the 1st Tuareg uprising in the 90s and was also a member of Muammar Gaddafi’s Islamic Legion. Ansar ad-Din allied with the MNLA, demanding the separation of Azawad from Mali, as well as the establishment of Sharia law throughout Azawad. Ag Ghali now heads the jihadist group Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), which is part of al-Qaeda. Since November 2017, JNIM has been collaborating with the Islamic State in the Sahel (ISSS), a regional branch of IS. There are at least five cases where groups acted together.

The Tuareg factor in Libya today

In January 2019, when Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army began its advance into southern Libya during the Second Civil War in Libya, Kanna called on the Government of National Accord to dissuade Haftar from destabilizing the Fezzan region. In February 2019, Fayez al-Sarraj appointed Kanna as commander of the Fezzan region. His role was in protecting the El Sharara oil field from being captured by Haftar and uniting the Tuareg and Toubou militias against Haftar. In November 2019, Kanna criticized southern militants who supported Haftar’s campaign in Western Libya and called on them to leave immediately. The Kanna’s Tuareg brigades still control Ghat, Ubari, Murzuk, and the Issine border crossing (the southern border crossing between Libya and Algeria).

Now the Libyan Tuaregs are concentrated mainly in the southwestern part of the country, in Fezzan, on the border with Algeria and Niger, where related Tuareg tribes also live. Despite the fact that the Tuareg factor in Libya itself is not as active as violence from jihadist groups, the Tuaregs can be used by Atlanticists for attacks primarily in Mali and Niger. The Tuaregs coming from Libya and Algeria organize sabotage and terrorist attacks against the current government of Bamako.

One of the options for further resolving the Tuareg problem could be to grant them autonomy without territory, which would give them the required freedom and allow them to maintain a nomadic way of life. Such autonomy implies the unification of citizens who identify themselves as belonging to a certain ethnic community. This is exactly what the Goïta government in Mali offers to them instead of Algiers Accords of 2015. This requires Tuareg leaders, including Ag-Ghali, to break away from French-American influence and negotiate with Bamako.

This scenario can be fully guaranteed by the integration of such autonomy within the Alliance of Sahel States from Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, as well as the development of constructive relations of the new confederation with Algeria and Libya. Most Tuaregs live on the territory of the Alliance countries and move between them, and the three states are now entering a period of active cross-border cooperation, which contributes to the intensification of political, economic and sociocultural ties.

Leave a Reply