By Dr Franklin Nyamsi

President, Institut de l’Afrique des Libertés / African Freedom Institute

In a study[1] published on June 19, 2023 on the reference site of the Egmont Institute, based in the capital of the European Union and NATO, Brussels, a duo of researchers from this organization set out to analyze the correlation between the action of the UN Security Council and the future of MINUSMA (United Nations Stabilization Mission in Mali). The authors conclude that, in the face of the Malian government’s request to withdraw “without delay” from MINUSMA, as expressed to the UN Security Council by its Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop on June 16, 2023, any decision by this body in line with the demands of Mali’s Transitional Government would be detrimental in the short, medium or long term, not only to the work of UN peace missions in Africa and around the world, but also to the civilian populations of Mali. In this critical analysis of the said study, we intend to show that the researchers at the Royal Egmont Institute, whose monarchist fascination is at odds with their claim to defend democratic values, are seriously mistaken: a) about the results of MINUSMA’s action against terrorism in Mali; b) about the nature of President Assimi Goïta’s Transition regime in Mali; c) about the real internal and external political implications of the demand for immediate withdrawal of UN forces from Mali’s African soil.

I

On MINUSMA’s 10-year assessment of the situation in Mali, from 2013-2023, the Egmont Institute’s false basic data

Let’s start by showing that the Egmont Institute’s scientific database on the situation in Mali is false, if not non-existent, so its conclusions could only be erroneous, especially when the two scientists claim without batting an eyelid that MINUSMA has really tried to stabilize Mali. Worse still, they claim “there is no doubt that MINUSMA has been working to reduce violence against civilians over the past decade”. None of this is supported by any material evidence, figures or mapping of the situation in the country at the time of MINUSMA’s arrival, on the one hand, and at the time of the advent of the Transition Regime, on the other. Such an approach to the problem is clearly intellectually frivolous. How can you judge a situation if you don’t know the facts?

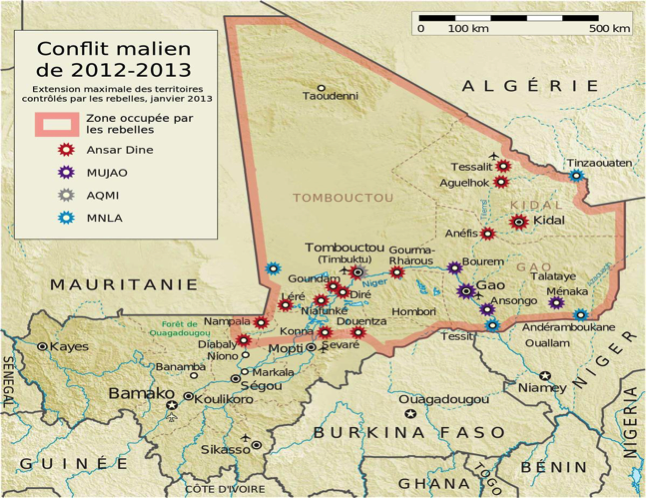

MINUSMA was set up in Mali in 2013 with the principal mandate of supporting the country’s security forces to protect[2] the population against terrorism and fully restore the authority of the Malian state throughout the country. Now, it’s worth remembering that in January 2013, only part of northern Mali was under attack from Al Qaeda and Islamic State armed terrorist groups.

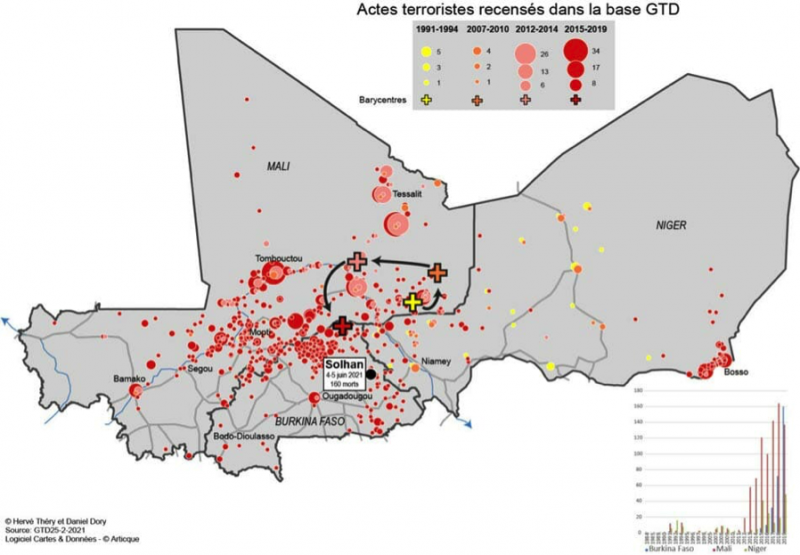

In 2020, at the time of the first coup d’état against the ineffectual, corrupt and puked-up regime of Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in Mali, completing a popular revolution against the failure of his regime, almost eight years later, what was the situation in which Mali found itself? The whole of Mali was affected by the criminal actions of terrorist groups. If we claim that MINUSMA and IBK’s[3] democratically-elected government have done their job rather well, how can we explain the scale of terrorist attacks across the whole of Mali?

Let’s take a close look at two maps, one showing the situation at the time of MINUSMA’s arrival, and the other showing the situation almost 10 years after MINUSMA’s arrival.

Source: Cartes et Données Arctique software

MINUSMA’s effectiveness is thus more in the expansion of destabilization than in the stabilization of Mali. It is therefore understandable that the French press, just 5 years after the arrival of the French army and MINUSMA to Mali’s rescue, back in 2018, could write:

“Mali, a war without end. Five years after the French intervention, which drove the jihadists out of northern Mali, terrorist attacks are multiplying and whole areas of the country are escaping the control of Malian and UN forces.”[4]

And to add on April 30, 2018 under the alert pen of Philippe Martinat in Le Parisien:

“How do we get out of this? More than five years after the French intervention in Mali to halt the spread of jihadists, and after the deployment of Barkhane (the 3,000-strong force that took over from Serval) and MINUSMA (the United Nations Integrated Mission for the Stabilization of Mali), chaos still reigns. Proof of this is the killing this week of some forty Tuareg civilians, including elderly people, women and children, in the north-east of the country, on the border with Niger. Or the spectacular attack on the joint MINUSMA and Barkhane base in Timbuktu on April 14, described by military authorities as “unprecedented”.

The 12,000 peacekeepers deployed seem powerless. Harassed by jihadists, they hardly leave their barracks. The Malian armed forces (Famas) are still struggling to establish themselves on the ground, and there is a certain amount of porosity between the armed groups involved in the peace agreements with the Malian state and the terrorist movements affiliated to al-Qaeda or Daech, which have only a few hundred permanent fighters but have undeniable relays in the population”.

From the above, no scientific research team worthy of the name can therefore conclude, as the researchers at the Royal Egmont Institute do, that MINUSMA has successfully carried out its mission in Mali, and that the two military coups of 2020 and 2021 are the major causes of MINUSMA’s weakening, due to the restrictions on access, mobility and rotations imposed from 2021 onwards by the Malian Transition authorities. The massive failure of MINUSMA is an apodictic fact. Malian Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop was therefore perfectly right to observe June 16, 2023:

“Realism demands that we acknowledge the failure of MINUSMA, whose mandate does not meet the security challenge”.[5]

To claim, as our two eager researchers do, that since the main responsibility for the country’s security lies with the government, the latter must be held solely responsible for the failure of the fight against terrorism with MINUSMA and Barkhane, is a headlong rush that cannot obliterate the evidence of the failure of these security assistances. Better still, the triple failure of the IBK regime, the Barkhane force and MINUSMA to defeat terrorism in Mali over a period of ten years legitimizes the popular uprising and the two coups d’état of 2020-2021 as an outburst of pride by the Malian people in the face of imperialism. As the head of Mali’s diplomatic corps once again reminded us, a mission limited to peacekeeping can maintain nothing when war reigns.

II

The nature of the Mali Kura Transition Regime led by Colonel Assimi Goita, President of the Transition, Head of State

Showing great intellectual laziness, the researchers at the Royal Egmont Institute have no qualms about flatly repeating the concept of junta, which the French media and officials have attributed to the current Malian government. Strictly speaking, a military junta is a “group of high-ranking soldiers who seize political power”[6]. But there is a sovereignist extension of the junta concept in the Latin language itself, which our hurried researchers ignore or pretend to ignore. The Robert dictionary also reminds us that in Iberian countries, the notion of junta is not limited to its military meaning. The junta is “formerly, in Iberian countries, a political or administrative council, regular or revolutionary” In this precise sense, General de Gaulle and the French Resistance who founded the 5th Republic in ’58 were also a junta between 1940 and 1945 at least, since it was at the end of a revolutionary and putschist process that they overthrew the Pétain regime and ended up creating the current French Republic, having seized political power in France by force of arms.

In the specific case of Mali, the militaristic notion of a junta is no longer valid, since it is at the end of a popular revolutionary process against the regime of Ibrahim Boubacar Keita that Colonel Assimi Goïta, in phase with numerous movements strongly representative of Malian civil society such as Yèrêwolo Debout sur Les Remparts and the M5RFP, will successively take power in 2020 and 2021.

Far from being a reactionary coup d’état aimed at returning to an old order rejected by the people, far from being yet another action in the service of the interests of French neo-colonialism or the imperialism of the great powers of the East or West, the Mali Kura process that brought President Goïta and his companions to power is founded on quadruple legitimacy:

– Military first, because Assimi Goïta and his brothers-in-arms represent the conscious backbone of the Malian army that experienced the neo-colonialist humiliation of 2013 at the gates of Kidal, when it was, to its surprise, prevented by the French army from defeating the terrorists and driving them out of Malian territory forever.

– Secondly, popular legitimacy, because Colonel Goïta took power in step with the revolted Malian people, taking care to surround himself, via a civilian Prime Minister, with the support of most of the country’s patriotic and republican political class.

– Democratic legitimacy, as demonstrated by the Refondation national conference in December 2021 and the large-scale mobilization of over 5 million Malians on January 14, 2022, in response to the illegal, illegitimate and inhumane sanctions imposed on Mali by ECOWAS on January 9, 2022, at the behest of Western powers, because of its decision to cooperate with the Shanghai Bloc (Russia, China) in the fight against terrorism, in place of NATO, the EU and France.

– Then, ideological legitimacy, due to the three pan-Africanist and sovereignist principles of Malian governance under President Goïta: sovereignty/freedom of geostrategic choice/vital interests of the people. All of this is in line with the pan-Africanist ideal of the founding fathers of African Unity, to which Mali’s constitution remains strongly attached, even in its new version to be put to referendum on June 18, 2023.

To claim, in the light of all the above, that President Assimi Goita’s regime is suffering from a crisis of legitimacy which the Security Council could rightly seize upon as an argument not to apply the demand for immediate withdrawal formulated on June 16, 2023 by the Head of Mali’s Diplomacy, is to be sadly mistaken about the popular, revolutionary, democratic and pan-Africanist nature of the current Transition Government. In reality, far from being a junta as the Françafrique press likes to denigrate it, the Mali Kura regime is the substantial emanation of the Malian people, as attested by the data from all the polls carried out on Malian territory by the German Friedrich Ebert Foundation[7], in its Malimeters 2022[8] and 2023[9] in particular. It is therefore astonishing that the so-called scientists gathered at the Royal Egmont Institute should completely disregard the data from authentic field studies such as those carried out by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung-Mali, and prefer the fictitious assessments of a team of UN investigators who never set foot on Malian territory before publishing their infamous report on the alleged massacre of 500 Malian civilians in Moura.

And if even the very Franco-African newspaper Le Monde felt obliged to acknowledge the massive popular support of the Malian people for Assimi Goita’s regime and its new Russian allies, how is it possible to understand why this strong socio-political fact is omitted from the Royal Egmont Institute’s analyses? Yet here, published on May 20, 2022 – as an illustration of the Malian embellishment under the Transition regime – is the summary of the Malimètre 2022 carried out by the German Foundation:

“Some 84% of Malians feel that the general situation in the country has improved over the past twelve months, according to the results of the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung’s 13th ‘Mali Mètre’ opinion survey, made public in Bamako on Thursday.

Over the same period, 8% of those surveyed felt that the situation in Mali had rather deteriorated. The same number of Malians believes that the situation has remained at the same level, according to the results.

This political opinion survey has been carried out in Mali since the end of 2012. It has gathered the opinions of Malians on a range of issues of current importance or decisive for the country’s present and future.

According to Christian Klatt, who presented the findings of the survey, the proportion of people believing that the country’s general situation has improved has increased by 50% compared to 2021 and by 58% compared to 2017. However, he pointed out, it is 20% below the statistics between 2019 and 2021.

In addition to the evolution of the country’s general situation, the opinion poll asked about the challenges currently facing Mali. On this subject, 76% of respondents said they were concerned about the fight against insecurity. While the fight against food insecurity worries 48% of respondents, the fight against youth unemployment is a major challenge for 41%. The fight against poverty focuses the attention of 40%.

These concerns remain almost the same as those raised over the last five years, noted the survey report presenter. Mali’s main challenges and priorities were the fight against insecurity, youth unemployment, food insecurity, poverty and the improvement of the education system.

Christian Klatt explained that more than nine out of ten people are satisfied with the management of the Transition, including 67% who are very satisfied and 28% who are fairly satisfied. Among the Transition authorities, the President of the Transition is the person in whom the people surveyed have the most confidence, with a rate of 72%.

With regard to international partners, Malians’ main expectations are: the fight against insecurity (75%), the fight against food insecurity (42%), the fight against youth unemployment (39%) and the fight against poverty (36%). More than half of those surveyed believe that inter- and intra-community conflicts are non-existent, notes the document.

The survey also looked at Malians’ main sources of information on current affairs. It found that 38% of Malians get their news from the radio, 27% from television, 11% from Facebook, 8% from websites and 8% by word of mouth.

The survey was carried out among 2,344 people aged 18 or over in the regional capitals and the District of Bamako from March 13 to April 4, 2022. The sample size was set according to the formula for estimating a proportion. Its final size took into account two other aspects: adjustment for low-weight regions and anticipation of non-response.

The sample was drawn in such a way as to ensure that it was representative of the population’s demographic structure. As a collection technique, the interviewers used the quota method with categories such as gender, age and level of education. The sampling plan adopted guarantees equal representation of both sexes (50% of the sample surveyed are women).”[10]

Clearly, the demonization of Mali’s transitional government by the Western press and the Egmont Royal Institute study we are criticizing is nothing more than a form of score-settling under the guise of democracy and humanitarianism, by a Western political elite which considers that the disavowal of the African policies of NATO, France, the UN, the AU, the EU or ECOWAS by the conscientious popular masses of West Africa and by pan-Africanist regimes sounds the death knell for centuries of Western hegemony.

It remains, in these clarified conditions, to reassess the internal and external significance of Mali’s decision to order the immediate withdrawal of MINUSMA from Malian soil.

III

Internal and external implications of Mali’s decision to order the immediate withdrawal[11] of MINUSMA from Mali

The Egmont Institute’s criticized study gives the impression that Mali’s decision is a serious attack on the UN’s prerogatives, on the interests that would be linked between MINUSMA and Mali’s civilian populations. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Firstly, because the UN Charter does not abolish the inalienable principle of the sovereignty[12] of peoples, whether expressed by a Transitional Government or by a revolutionary uprising of the People. By virtue of this principle, the Government, the State and the People of Mali are entitled to demand the departure of foreign troops present on their soil at any time in their existence.

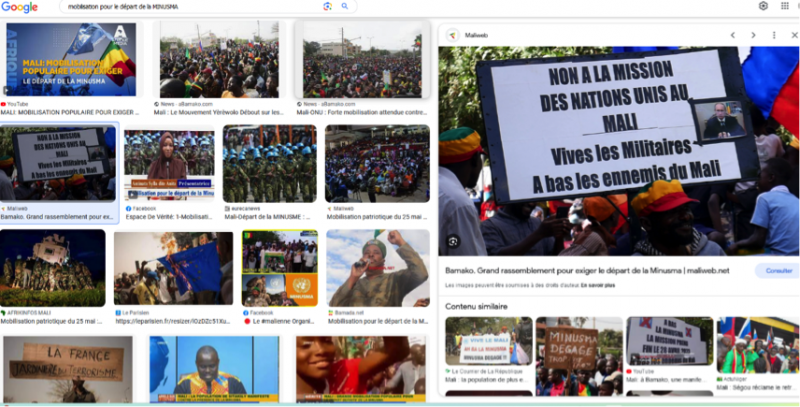

The Malian people have actively seized this sovereign right and are exercising it to the full, from the streets to the ballot box, from the towns to the countryside. From this point of view, the researchers at the Egmont Institute pretend to ignore the fact that the departure of MINUSMA is first and foremost the broadest and largest popular demand[13] in Mali, after the departure of French forces and foreign troops. Several popular mobilizations have taken place across the country to demand that the UN withdraw its useless contingents from the fight against terrorism. How can these Western researchers ignore all the mobilizations against[14] the presence of this MINUSMA?

From an internal point of view, this decision to order the immediate withdrawal of MINUSMA confirms the symbiosis between the people, the State, the army and the Transitional Government of Mali. It meets the aspirations most widely shared by the Malian people, and confirms the internal legitimacy of President Assimi Goïta’s regime.

But what about externally? What will be the international consequences of Mali’s sovereign, sensible and internally consensual decision to ask UN soldiers to withdraw without delay? The experts at the Royal Egmont Institute imagine three scenarios, all of which they consider to be fraught with consequences.

The first option, they tell us, would be to renew MINUSMA’s mandate, arguing that the Transitional Government, despised under the concept of junta, is not the emanation of democratic sovereignty and would therefore have no title to decide on behalf of the Malian People. Of course, such a solution would have to avoid a Russian or Chinese veto on its way to the UN Security Council at the end of June 2023. But assuming that the renewal goes ahead, our experts – rather blinkered in their lucidity – are quick to point out that this would lead to direct conflict between the Goïta regime and UN forces. However, their reasoning proves to be short-sighted, as the Malian government is acting on the basis of broad popular support and massive mobilization of African opinion, which is strongly opposed to Western neo-colonialism and imperialism, but also to dictatorships supported by foreign powers hostile to Africa’s real independence. As a result, to refuse to leave is not only to run the risk of incurring the wrath of those in power, but also that of being ousted by an irrepressible popular mobilization supported by the authorities, who are themselves dependent on them. It would therefore be better for MINUSMA to leave, just as the UN has had to leave Burundi and Eritrea in the past, in relatively comparable circumstances.

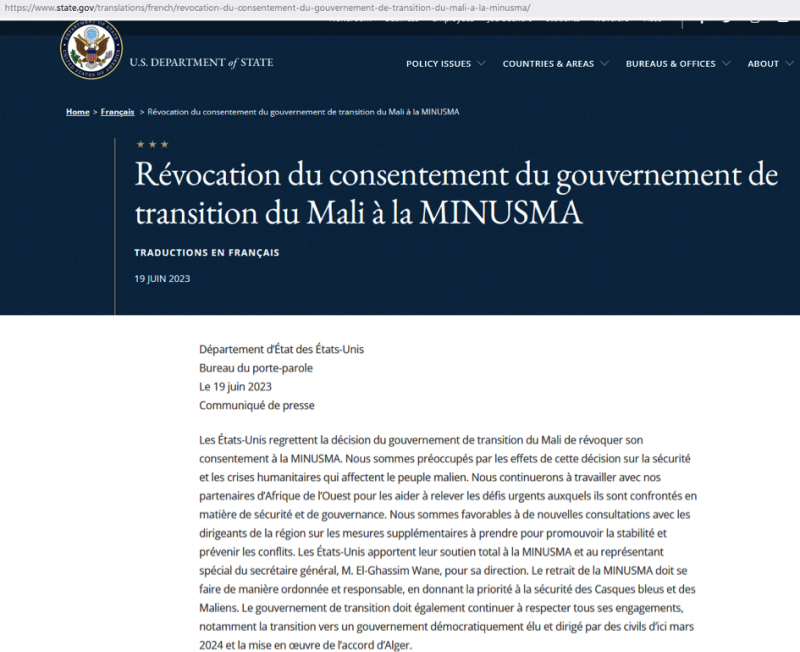

The second option, we are told by the sharp-shooters in Brussels, would be to withdraw MINUSMA in line with Mali’s sovereign demands. Or, alternatively, not to renew MINUSMA’s mandate, which would entail its immediate withdrawal. This is the only option that respects the sovereign expression of the Malian people. But our experts in Brussels, preoccupied with saving Western hegemony at all costs, taste it with bitterness and see it as an unfortunate precedent that would give the juntas the power to dictate their four wills to the sacrosanct UN, with the support of the no less demonized Russia with its Wagner militia. And yet, how many punitive resolutions has the UN passed against Western war crimes in its nearly century of existence? What about the many UN resolutions that have fallen at Israel’s feet in the Palestinian crisis? How many UN resolutions against the support of many Western powers for the world’s worst dictatorships? The “double standards” of the royal experts in Brussels, curiously subjects of their hereditary monarchical majesties and concomitant defenders of democracy, is simply blatant here. As is their refusal to take into account the undeniable popular base of Mali’s current transitional regime. It is therefore clear that the UN has no choice but to respect the sovereign choice of the Malian people. The US State Department seems to have understood this to a certain extent, in its statement of June 19, 2023, which we reproduce below, while of course suggesting that it should always be taken with a grain of salt:

In acknowledging “the withdrawal of MINUSMA must be carried out in an orderly and responsible manner…”, the leader of the Western bloc seems to be taking it on the chin – and we do mean “seems” – all the more so as he is aware of the 3rd scenario evoked by the Brussels researchers, which recognizes the diplomatic weight acquired by leader Assimi Goïta’s Mali following its change of geopolitical and geostrategic course in favor of closer security cooperation with the powers of the Shanghai Bloc and, more broadly, the multipolar world.

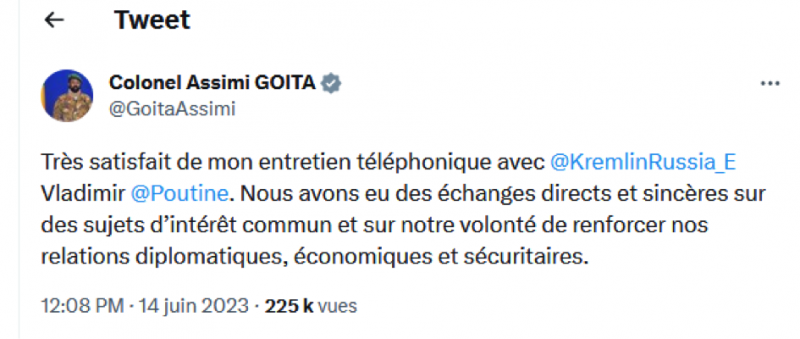

According to the third and final scenario envisaged, Russia, Mali’s main and powerful ally, which was amply consulted by Mali before the start of UN hostilities in June 2021, would firmly veto the renewal of MINUSMA, following Mali’s sovereign decision announced on June 16, 2023. Russia would thus be following in the footsteps of Burkina Faso, which immediately after the announcement of Mali’s decision showed its readiness to respect the sovereignty of its ally in Bamako, by announcing the imminent withdrawal of its contingent from MINUSMA. Better still, by blocking the resolution renewing MINUSMA with its powerful veto, Russia would be assuming, as it did in 2009 in the case of Georgia, a division of the UN Security Council, also consecrating the challenge to the unilateral and multi-secular hegemony of the West over international relations. Doesn’t the tweet below from Malian President Assimi Goïta seem to confirm this shared determination, as does the intense prior consultation observed between the head of Malian diplomacy and the Russian ambassador to the UN, Vassili Nebenzia? What happens next in the month of June 2023 will soon tell the tale. On June 14, 2023, the Malian Head of State tweeted the following:

And ahead of his June 16, 2023 appearance at the UN Security Council, Ambassador Abdoulaye Diop, Mali’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, commented on his preparatory meeting with Russia’s UN representative:

All in all, it is inconceivable that the Royal Egmont Institute’s study should have sought to portray the current Malian authorities as marginal and irresponsible decision-makers who would place themselves at the mercy of international law by demanding the immediate departure of MINUSMA from their soil. This departure is necessary because MINUSMA is not fighting terrorism. This departure is legitimate because MINUSMA, by participating in the instrumentalization of democratic and humanitarian themes, has in the meantime become part of the daily destabilization of Mali, directly or indirectly. This departure is timely, because the geopolitical and geostrategic alignment of the Malian people and the majority of African peoples for the true sovereignty of the continent is a real, vital and irrepressible aspiration, which all reliable scientific analysis tools point out. The Royal Egmont Institute’s pseudo-scientific support for Western imperialist powers operating through the “order through chaos” method must therefore be denounced and demystified, to foster the birth of a truly equitable, shared, prosperous and reasonable world for all human generations, now and in the future. This critique serves this hope, for as the philosopher Gaston Bachelard rightly reminded us:

“Knowledge of reality is a light that always casts shadows somewhere. It is never immediate and complete. The revelations of reality are always recurrent. The real is never “what one might believe”, but it is always what one should have thought. Empirical thinking is clear, after the fact, when the apparatus of reasons has been perfected. By going back over a past of errors, we find the truth in a genuine intellectual repentance. In fact, we know against a previous knowledge, by destroying poorly made knowledge, by overcoming what, in the mind itself, stands in the way of spiritualization”.[15]

June 20, 2023

To contact the author: franklin.nyamsi@gmail.com

[1] https://www.egmontinstitute.be/the-un-security-council-and-the-future-of-minusma/

[2] https://news.un.org/fr/story/2023/06/1136182

[3] Ibrahim Boubacar Keita

[4] https://www.leparisien.fr/international/mali-une-guerre-sans-fin-30-04-2018-7691247.php

[5] https://www.france24.com/fr/afrique/20230616-le-mali-r%C3%A9clame-le-retrait-imm%C3%A9diat-de-la-minusma-la-mission-de-l-onu

[6] According to the French dictionary Le Robert https://dictionnaire.lerobert.com/google-dictionnaire-fr?param=junte

[7] https://mali.fes.de/mali-metre

[8] https://mali.fes.de/e/mali-metre-xiii

[9] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2023/05/04/selon-une-enquete-d-opinion-plus-de-neuf-maliens-sur-dix-ont-confiance-en-la-russie-pour-aider-leur-pays_6172044_3212.html

[10] https://www.faapa.info/blog/mali-metre-2022-la-majorite-des-maliens-satisfaite-de-la-gestion-de-la-transition-enquete-de-la-fondation-friedrich-ebert-stiftung/

[11] https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2023/06/17/le-mali-exige-le-depart-sans-delai-de-la-mission-de-l-onu_6178060_3212.html

[12] https://www.lopinion.fr/international/avec-le-depart-des-francais-du-mali-assimi-goita-prend-le-controle-des-airs

[13] https://www.dw.com/fr/mali-manifestation-anti-minusma-onu-yerewolo/a-63211406

[14] https://www.aa.com.tr/fr/afrique/mali-le-mouvement-y%C3%A8r%C3%A8wolo-d%C3%A9bout-sur-les-remparts-exige-le-d%C3%A9part-de-la-minusma/2884611

[15] Gaston Bachelard, La Formation de l’Esprit Scientifique, Paris, Librairie philosophique Vrin, 1999 (1ère édition : 1938), chapitre 1er.

Leave a Reply