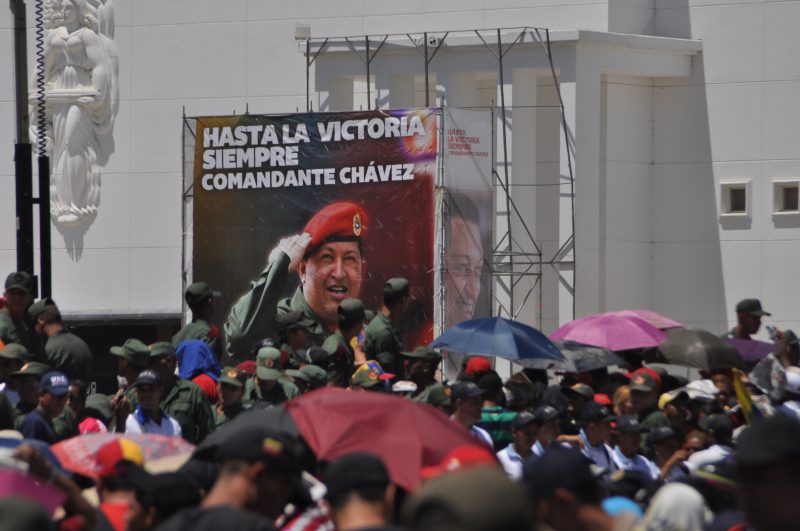

March 5 marks the 10th anniversary of the “physical departure” of Hugo Chávez, as his passing away is called in Venezuela and wide parts of Latin America.

United World International author Sergio Rodríguez Gelfenstein, who served as Director of International Affairs in the Venezuelan Presidency during Chávez’ government, has given an interview to the Spanish edition of Sputnik news agency on the leaders’ legacy in the continent.

UWI has translated the interview from Spanish and presents it as published by Sputnik.

Hugo Chávez proposed an infinite number of models for a real Latin American integration based on the principles of Simón Bolívar. Ten years after his physical departure, Chávez’s analyst and former adviser, Sergio Rodríguez Gelfenstein, told Sputnik how the character of the Venezuelan president marked an era for the continent.

Sergio Rodríguez Gelfenstein knew former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) well, since he served as director of International Affairs of the Presidency of Venezuela during his Government. For this reason, a decade after his death , the international relations expert can assure that the founder of Chavismo was not only “the greatest Bolivarian” but also the person responsible for planting the seeds of Latin American integration in the 21st century .

A review of the history of Hugo Chávez shows how the commander derived from a program of proposals focused on changing the Venezuelan reality to develop a broader political vision with which he sought for Venezuela to have a leading role on the regional and global scene.

In a conversation with Sputnik, Rodríguez Gelfenstein recalled that foreign policy “was not an issue of the first order” for Chávez in 1998, when his campaign to gain access to the Government focused on recovering the Venezuelan oil industry, combating the prevailing corruption until then and convening a Constituent Assembly.

However, the expert recalled, Chávez was “deeply Bolivarian in ideological terms”, which is why, once in government, he could not help but also begin to think about the fate of Latin America and the Caribbean as a region. Of course, it was not easy to do so in the last years of a decade of the 1990s marked by neoliberal ideas and the absolute hegemony of the United States in the decisions of the region.

“Chávez realized that the regional political dynamic was totally dominated by Washington,” explained Rodríguez Gelfenstein, recalling the Summit of the Americas held in Canada in 2001. There, the Venezuelan president found little harmony with the thought of Simón Bolívar when Washington insisted on the formalization of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).

Rodríguez Gelfenstein pointed out that, when there was still more than a year to go before Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (2003-2011) took office in Brazil and Néstor Kirchner (2003-2007) did the same in Argentina, “there was no correlation of forces” in the region that would allow his ideas of integration to find an echo. Even so, Chávez made up for the lack of complicity with other leaders by approaching the Latin American popular movement, something that would not fail to characterize him in the future.

At this stage, Chávez begins to understand that “if he wants to advance in a Bolivarian integration project, he must go through a confrontation with the US, which until then imposed the Monroe Doctrine ,” the analyst explained.

The expert emphasized that the disputes with Washington, which would characterize Chávez’ foreign policy from then on, were not sought by the Venezuelan, but by the US, which “saw the danger that Chávez represented for its interests.” The commander would fully understand how undesirable he would be for the White House when he suffered a coup attempt in 2002 that Venezuela maintains to this day was supported by the Americans .

ALBA, CELAC and Unasur: Organizations promoted by Chávez

One of the institutional expressions of Chávez’s integrating thought can be found in the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), a regional bloc devised by the Venezuelan leader with the support of Fidel Castro from Cuba, as a kind of opposition to the FTAA.

The organization, which brings together Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Cuba and several Caribbean countries, was born with the ideas of Bolívar, José Martí and Augusto Sandino, among other Latin American heroes who advocated integration that would counterbalance US influence.

However, Rodríguez Gelfenstein remarked that Chávez’s ideas of integration transcended ALBA, which only concentrated a few countries. “Chávez had a totalizing thought, he had a much broader vision of integration and he understood that he had to incorporate other countries,” he explained.

This explains the key role of the Venezuelan leader in the creation of CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) in 2011, an unprecedented relationship experience between all South American countries outside the Organization of American States (OAS).

The same with the founding of Unasur, a bloc that brought together all the South American states and was born in 2008, and Chávez’s insistence that Venezuela join Mercosur, the commercial bloc that until then only included Argentina, Brazil , Paraguay and Uruguay.

Rodríguez Gelfenstein recalled that Chávez saw Argentina and Brazil “in strategic terms” as decisive partners for true Latin American integration, even though the new progressive leaders who were coming to power in the early years of the 21st century were not yet “imbued” with that spirit.

As an example of this, the Venezuelan expert recalled the relationship between Chávez and Néstor Kirchner. The Argentine had come to the Government without much international experience, but he quickly forged what Rodríguez Gelfenstein considered “a very solid friendship” with Chávez that would place him as another of the referents of those integration processes.

With Lula, the harmony was also immediate, recalled the expert, pointing out that the Brazilian president had come to power with the firm conviction that Brazil would stomp on the international scene and begin to have influence in areas of the world where it did not. “Lula’s interest met with Chávez’s, Kirchner’s and Fidel’s and due to different circumstances an interest in integration is developing,” he stressed.

The Venezuelan analyst emphasized that Chávez knew how to transform this desire for integration into concrete measures, some of which are still mentioned as possible solutions a decade after his death. Chávez came to propose the sucre as the only Latin American currency and created the Bank of the South as an instrument to protect the financial sovereignty of Latin American countries.

Energy and fluvial integration, Chávez’s great dream

But, in addition, the former Venezuelan president defended the need for energy integration in Latin America , an issue that is increasingly becoming a serious problem for the countries of the region.

“Chávez believed that a network of oil pipelines could be generated that came from Mexico and converged with Venezuelan gas pipelines in Colombian territory and then skirted the Pacific to the south and connected to Bolivian and Argentine gas pipelines, in order to produce a true integration that would make Latin America and the Caribbean independent in energy matters,” explained Rodríguez Gelfenstein.

For the analyst, it was “the oligarchies” of the countries of the region that paralyzed this project and prevented Latin America from currently having a better defense against the increase in energy costs.

In any case, a sample of the smaller-scale idea of Chávez’s energy integration can be found in Petrocaribe, an alliance that allows Caribbean countries to acquire Venezuelan oil at preferential prices.

Chávez also had another “great dream”: to connect the countries of South America through their rivers. “I was convinced that it was possible to make a fluvial connection through the Orinoco, Río Negro, Amazon, Pilcomayo, Paraná, and Uruguay rivers and reach the Río de la Plata to be able to communicate not from the outside, but from the inside. of the continent”, explained the expert.

Having worked closely with Chávez allowed Rodríguez Gelfenstein to verify the level of passion that the Venezuelan commander had with his projects.

“Chávez had some maps in his office where his entire idea of energy and fluvial integration was. It was something permanent in his ideas: economic, financial, energy, fluvial integration and even the acquisition of Latin American and Caribbean citizenship,” he summarized.

The character, a trademark of Chávez

Having known him closely, Rodríguez Gelfenstein maintains the conviction that the “humanist spirit” that the Venezuelan president gave to what he did was key to the development of his political platform. “The things that happened in Africa or Haiti hurt him and that pain not only remained in feeling, but he tried to do something that would express the solidarity of Venezuela,” he said.

For this reason, in addition to the integration mechanisms that he promoted, Chávez also shouldered, along with Fidel Castro, programs such as Operation Miracle, which led Cuban doctors to perform ophthalmological operations on low-income people throughout the continent.

In addition, the combination of high military studies with his humble origins fueled a charisma that allowed him to be a “natural leader” both for the Venezuelan Armed Forces and for workers and disadvantaged sectors of Venezuela. “Chávez was not oblivious to the feeling of the authentic Venezuelan,” summed up the analyst, highlighting the leader as a faithful representative of the “natural value of the Venezuelan people.”

This way of being also led him to stand firmly in international summits, either to argue with King Juan Carlos of Spain at a summit in 2007 or to go down in history by saying “yesterday the devil was here. It still smells of sulfur”, at the United Nations Assembly in reference to US President George W. Bush (2001-2009).

“Chávez felt the responsibility of having been elected president, and in those international events he manifested that pure feeling of the Venezuelan. And he was not afraid. He was not afraid because he had very deep convictions,” emphasized Rodríguez Gelfestein.

The legacy lives in the peoples

A decade after hic phsyical departure, Chavez’ ideas are more than alive in those countries that have followed them the most, such as Venezuela itself, Cuba, Nicaragua or several Caribbean countries, assures the expert. In any case, he admitted that “the situation in the region today is different.”

“Today’s left are not the same as twenty years ago, today’s Lula is not the same as twenty years ago, and Alberto Fernández is not Néstor Kirchner. We cannot make a comparison,” he lamented. He even admitted that the current Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro, has had to face “a brutal blockade” that did not have the same force in the Chávez era and that also conspires against Venezuela’s influence in the region.

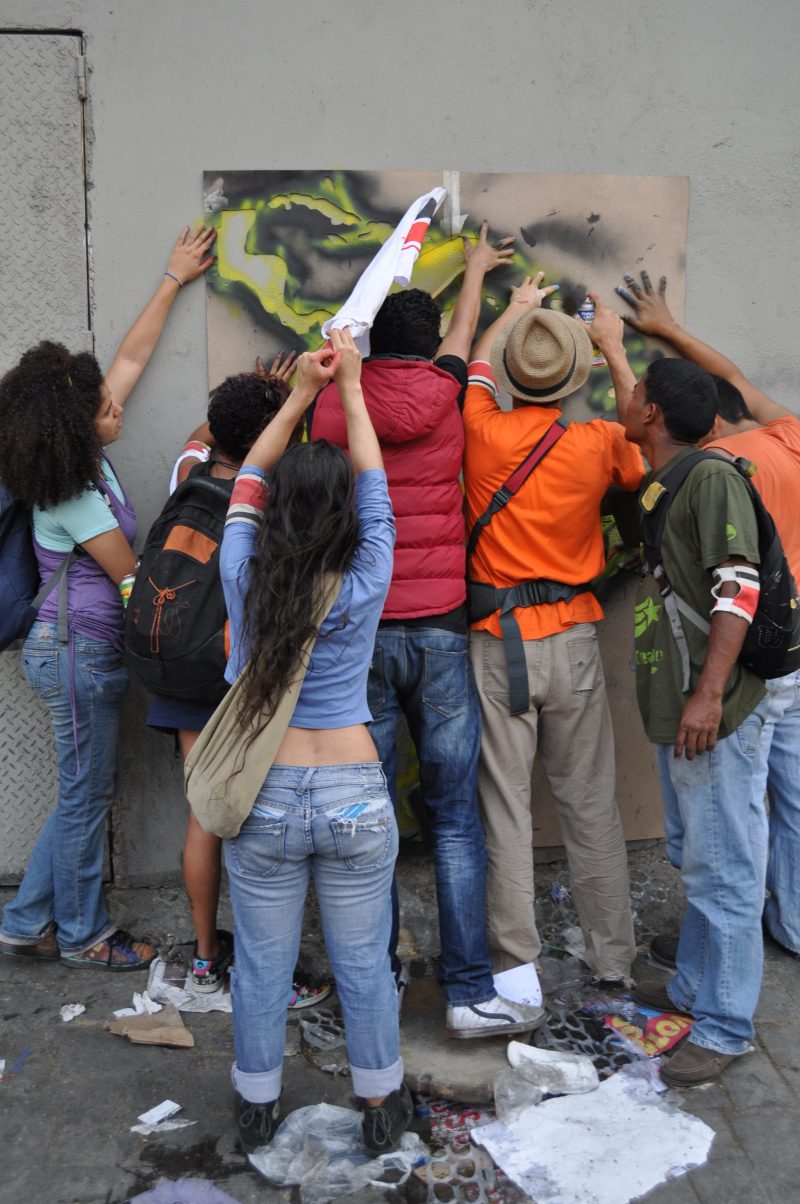

However, Rodríguez Gelfenstein assured that the legacy of Hugo Chávez can be seen with greater evidence in the popular sectors of Latin America.

“The spirit of Commander Chávez is in the people, who have an extraordinary memory of his imprint. I think it is impossible to hide Chávez from history, he is an everlasting actor facing the future and the history of Latin America,” he summarized.

Leave a Reply