by Ana Dagorret / Rio da Janerio

After an election day that showed a completely divided country, Brazil is heading to a runoff election between Lula Da Silva and Jair Bolsonaro. Although polls of voting intention showed a possibility of victory for Lula already in the first round, with more than ten points of advantage over the current president, the growing support for Bolsonaro in the final stretch and the good performance of several of his candidates managed to shorten the distance to five points and force a second round.

The result, despite showing a victory for Lula, leaves a bitter feeling. Not only because it pushes the country into four more weeks of political campaign, where Bolsonaro will try to reverse the trend to get himself reelected, but also because the election for deputies, senators and governors shows a gloomy panorama, with Bolsonarism growing in number of representatives.

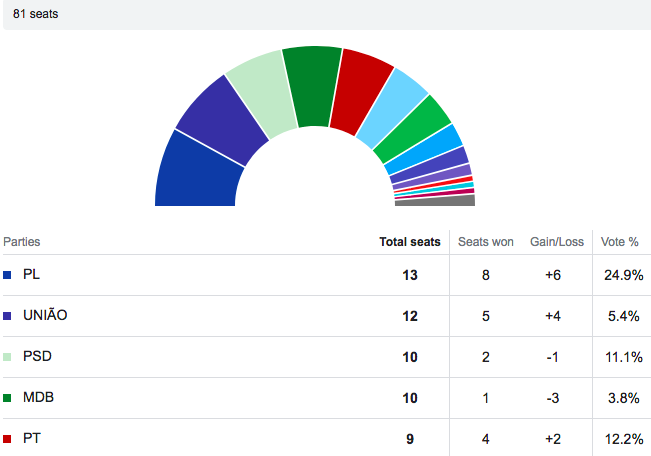

In the south of the country, former Lava Jato judge and Bolsonaro’s former Minister of Justice, Sergio Moro, was elected senator for Paraná. In São Paulo, the Minister of Science and Technology of the current government, Marcos Pontes, also won a seat in the Senate. Bolsonaro’s Minister of Women, Family and Human Rights, the controversial Damares Alves, was also elected to the Senate for Brasília, as was Pastor Magno Malta, very close to the President, for the state of Espiritu Santo. Vice-president Hamilton Mourão was elected for Rio Grande do Sul.

With these names in the upper house, Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party now has the largest Senate bench, while the rest of the seats are in the hands of a conservative majority and some names from the left.

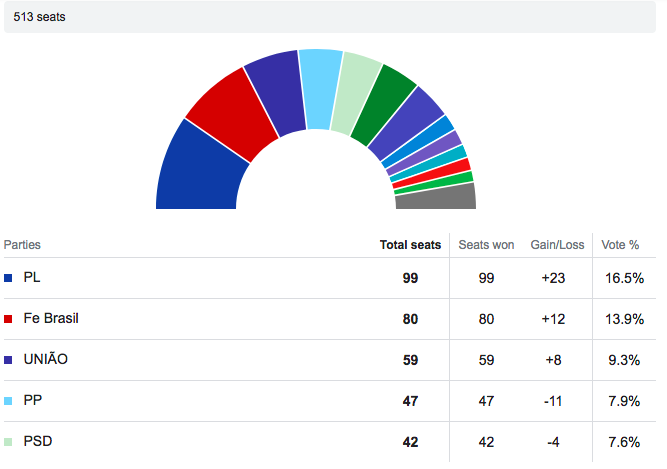

Bolsonarism’s success in Congress

In addition to the Senate, Bolsonarism won an expressive election in Congress. Most of the candidates for reelection of the so-called Centrão achieved their goal, while names such as General Eduardo Pazuello – former Minister of Health who left the city of Manaus without oxygen during the pandemic, causing dozens of deaths by asphyxiation – was the most voted candidate for deputy in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Rio was also the scene of the victory of the Bolsonarist governor Claudio Castro in the first round, in what the polls predicted to be a head-to-head dispute with the left-wing candidate Marcelo Freixo, who was more than 30 points behind the current governor. In Sao Paulo the dispute also turned out to be a surprise. Bolsonarismo candidate Tarciso de Freitas won first place against all odds and will dispute the second round with PT candidate Fernando Haddad, in what is expected to be one of the most difficult elections for the opposition.

Although the possibility of achieving victory in the first round seemed difficult and the result gained by Lula was expressive, the visible panorama after the election generates enormous confusion. After four years of increasing inequality, growth of poverty rates, dismantling of the education and public health systems and a ‘negationist’ health policy that led the country to count about 700 thousand deaths during the pandemic, Bolsonaro still has gained 51 million votes (2 million more than in 2018). This indicates a trend. Similarly, several figures of his government linked to the most ideological wing have conquered legislative positions – a fact that speaks of a deepening of the conservative wave that is installed as a response to the attempts of the left to gain more ground.

All this anticipates a complicated scenario regardless of who assumes the presidency as of 2023. If Lula wins on October 30, he will have to govern with a Congress that has broadened its conservative base. Beyond his unquestionable capacity for political articulation, Lula could be subjected to negotiate positions and budget to ensure his governability, which would limit him even more in a context where alliances with center and right-wing sectors to win the election already express certain conditions.

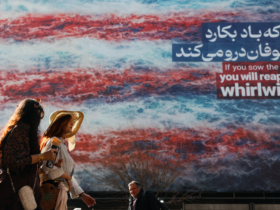

Similarly, should Lula win, he will face the task of governing a deeply divided society, where hate speech and political violence have become key factors in current politics and in Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign for reelection.

With less than 30 days to go before the second round, the challenge for Lula and the Workers’ Party is to consolidate the numerical victory obtained in the first round. Although there is no record of a rebound that has allowed the runner-up to win in the second round in Brazilian democratic history, Bolsonaro’s power project and the use of the State in his favor to achieve reelection at any cost show the difficulty of foreseeing an outcome.

Previously published in spanish by Noticiaspia.com. Translation by UWI.

Leave a Reply