By Michael Roberts *

Japan’s prime minister Fumio Kishida comfortably won last October’s general election for the lower house of the Diet for the ruling Liberal Democrats (albeit with a slightly reduced majority). And he is headed for victory in this Sunday’s upper house election, likely to extend the number of seats it holds to 60 out of 125 contested. So politically, Kishida is in a strong position. (The article was written before the elections. The LDP won 63 seats gaining majority, UWI.)

Former banker Kishida campaigned on a program that he claimed was going to revive the Japanese economy with what he called a “new capitalism”, supposedly a rejection of ‘neoliberalism’ as operated by previous PMs like Abe. Instead, he would reduce inequality, help small businesses over the large and ‘level up’ society. This would break with Abe’s emphasis on ‘structural reform’ ie reducing pensions, welfare spending and deregulating the economy.

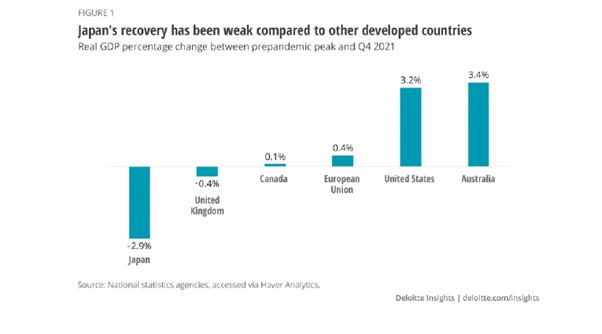

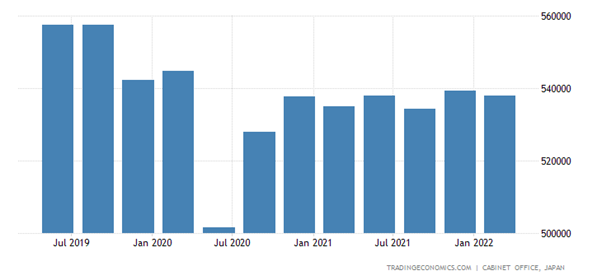

How is ‘new capitalism’ doing in Japan after eight months? Not too well. The Japanese economy contracted in Q1 2022. Record Covid-19 case numbers led the government to introduce quasi-state-of-emergency measures, which along with rising inflation caused private consumption and investment to fall. In Q2, the economy was still struggling. Export growth and manufacturing activity are still sliding, due to supply bottlenecks and a slowing global economy due to war in Ukraine, Covid-19 lockdowns in China and higher global inflation and interest rates. Indeed, real GDP was still 2.9% below its pre-pandemic peak at the end of 2021 when Kishida took over. That’s a weaker performance than most developed economies. And there has been no improvement in 2022.

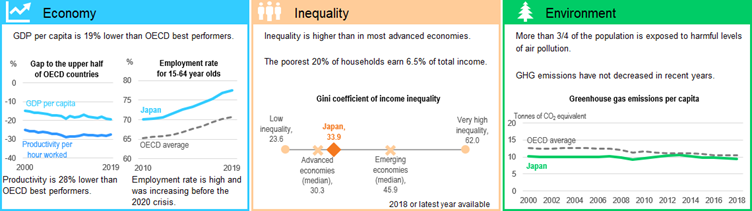

Indeed, according to the OECD, Japan’s GDP per head is still nearly 20% below its G7 leaders; inequality of income remains higher than in most advanced economies; and pollution and greenhouse gas emission are still way too high compared to Paris climate change targets.

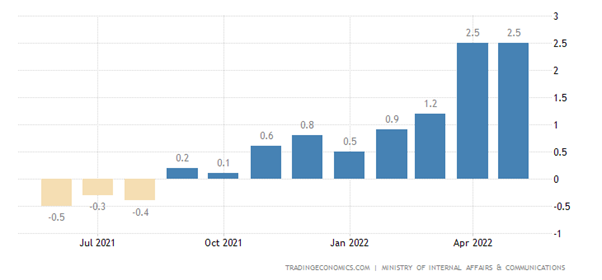

Japan has suffered the same shocks that have affected the global economy amid a surge in oil and gas prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But while consumer price inflation has soared above 8% in the US and the UK, Japan’s headline inflation has risen to only 2.5%.

Why is that? It’s mainly because the Japanese economy remains in the doldrums, continually teetering on outright recession. So investment and consumer demand is weak.

This is particularly the case with wages. Wages even in nominal terms are no higher than before the start of the Great Recession in 2008.

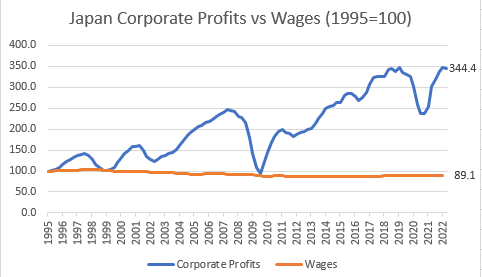

Indeed, it has been a feature of the last 25 years that wages have remained stagnant while profits have risen.

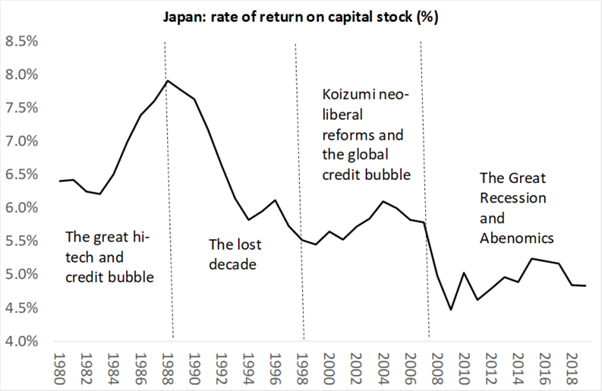

This is the product of the neo-liberal policies adopted by successive governments, trying to reverse the long-term decline in the profitability of Japanese capital, with only limited success.

Japanese workers have paid for these higher profits during the Long Depression of the last decade. Even the Bank of Japan governor admitted as much. Kuroda said persistent deflation between 1998 and 2013 had made companies cautious about raising wages. “The economy recovered and companies recorded high profits,” he said. “The labour market became quite tight. But wages didn’t increase much and prices didn’t increase much.” No wage-price spiral in Japan.

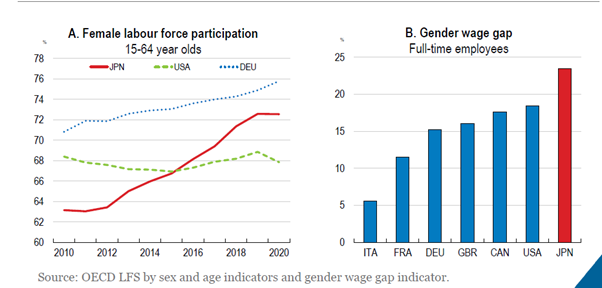

Even though the official unemployment rate is near all-time lows, as in other major economies, there is more ‘slack’ in the labor market than the 2.7% unemployment rate would otherwise indicate. The aggregate number of hours worked is still 2.8% below the level seen two years earlier. And companies are filling gaps in the ranks of their workforces with part-time workers at lower wages. Unemployment is low because of the massive shrinkage in the working-age population, now declining at about 550,000 per year. The impact on the labour market has been compensated for by a sharp rise in female employment, but female employees work in lower wage areas and receive lower wages than males. This keeps wage pressure down and profits up.

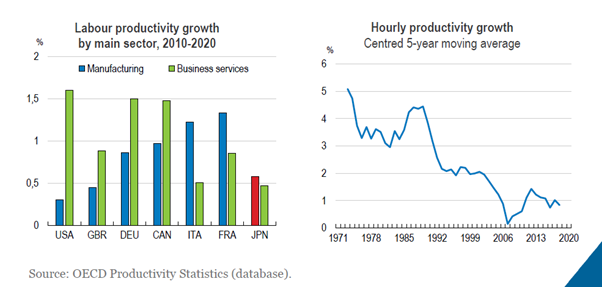

Those in work are overworked. Japan invented the term karoshi — death from overwork — 50 years ago following a string of employee tragedies. Kishida and the large corporates are promoting the idea of a four-day week to relieve this pressure and increase productivity. But there is little sign that this or any other measure is working to raise productivity. Productivity growth continues to slow; Japan has been one of the poorest performers for labour productivity in the last ten years.

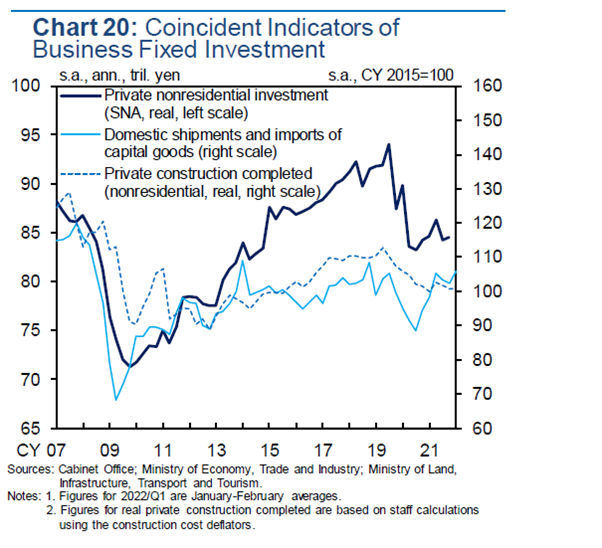

The reason is clear. Business investment growth is very weak. Japan’s corporations may have increased profits at the expense of wages and even managed to raise the profitability of capital a little, but they are not investing that capital in new technology and productivity-enhancing equipment. Real investment is no higher than in 2007.

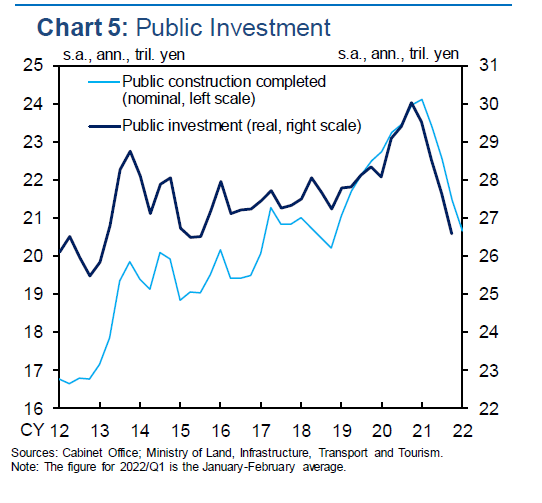

And public investment (about one-quarter of business investment) is static.

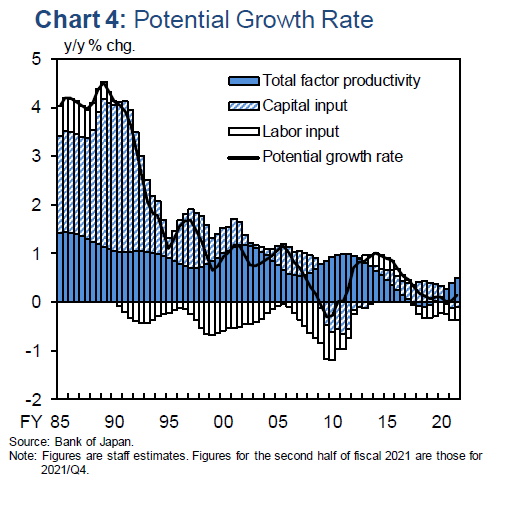

Japanese capital’s image of innovating technology appears to be long gone. A mainstream measure of ‘innovation’ is called total factor productivity (TFP). TFP growth has faded from over 1% a year in the 1990s to near zero now, while the huge capital investment of the 1980s and 1990s is nowhere to be seen. Now Japan’s potential real GDP growth rate is close to zero.

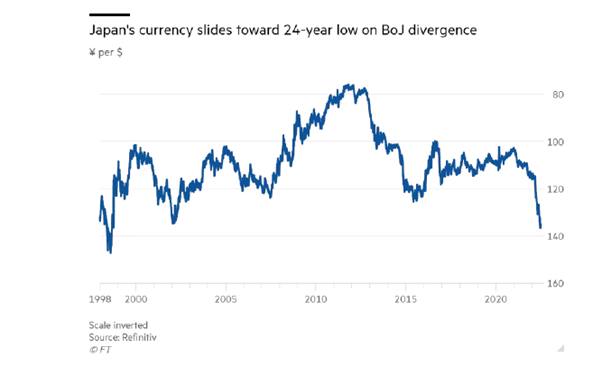

Low wage growth, near stagnation in economic activity and productivity; and a falling workforce; driven by weak investment and falling profitability; have meant that the Bank of Japan has had to keep interest rates close to zero or even negative. This has led to a sharp fall in the yen’s price against other currencies. The yen is now near a 24-year low against the dollar.

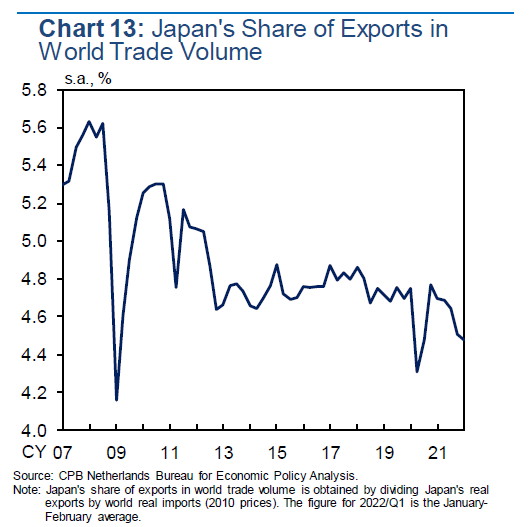

This should help exports in dollar terms. However, Japan’s famed export sector continues to lose ground in world markets, particularly as the auto sector is in deep crisis.

Japan’s ‘new capitalism’ under Kishida looks much the like the old, only worse.

* Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years. He has closely observed the machinations of global capitalism from within the dragon’s den. At the same time, he was a political activist in the labour movement for decades. Since retiring, he has written several books. The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He has published numerous papers in various academic economic journals and articles in leftist publications.

This article first appeared on Roberts’ blog and can be accessed here.

Leave a Reply