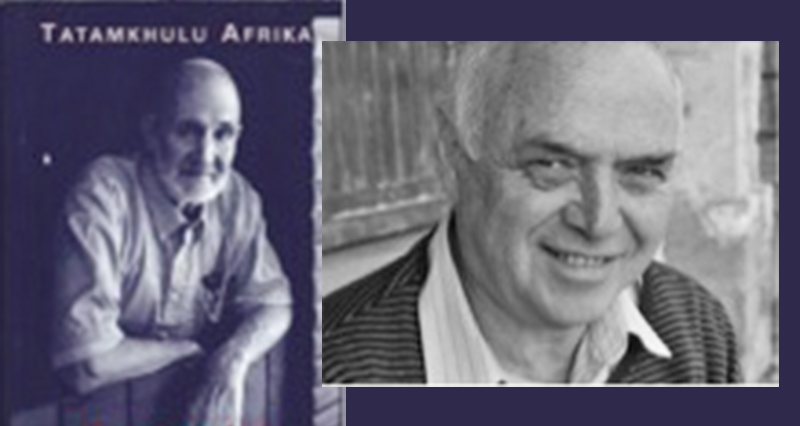

TATAMKHULU AFRIKA (1920-2002) was born in Egypt and came to South Africa as a young child. He fought in World War II and was taken prisoner. In the 1960s, he lived in Cape Town and converted to Islam, founding the armed resistance group Al-Jihaad. He published novels and novellas, and wrote two plays. He died following a road accident shortly after his 82nd birthday and the launch of a new novel.

Books of poems published:

Nine Lives (Carrefour/Hippogriff, 1991)

Dark Rider (Snailpress/Mayibuye, 1992)

Maqabane (Mayibuye Books, 1994)

Flesh and the Flame (Silk Road, 1995)

The Lemon Tree (Snailpress, 1995)

Turning Points (Mayibuye, 1996)

The Angel and other poems (Carapace, 1999)

Mad Old Man under the Morning Star (Snailpress, 2000)

Au Ceux (French translations) (Editions Creathis l’école des filles, 2000)

Tatamkhulu Ismail Afrika and Robert Berold

Your poetry has a tremendous range, some of it introspective, some of it dealing with portraits, with moments of celebration, with place, with political events or events in prison. What links it all, for me, is an ability to observe. Most of us in South Africa don’t have very good powers of observation. Things are so difficult and painful around us that we tend to go around with an ideology which we use to filter our surroundings. You have a political commitment but you don’t seem to need an ideology to numb the impact of your environment. How do you manage to see the world freshly and clearly without getting cynical or overwhelmed about it?

If you admit to yourself you’re all people too, then you have no armour between you and the people. Whenever I see a person who is unusual, I write a portrait of the person, a word portrait, so that I can remember that person as I saw him or her. I try to do it as accurately as I can. As I described it to Lionel Abrahams once, I lovingly circle the subject, fleshing it out bit by bit, until it stands before me as complete as I can get it. In that way I see each person freshly, newly, without prejudice, without reservation.

When it comes to writing about nature, I have a hunger. I was brought up on a farm and I love farm life. Sitting here in the city I long for greenery, for water — running water — and birds. I feed the doves out here in the yard. I planted my own little lemon tree and a fig tree in the concrete, so I can have greenery.

I’m pretty ancient by now, in my 72nd year, and well, at this age, one must be prepared to ‘shuffle off the mortal coil’ at any time. I think that I see things freshly because I realise I may be seeing them for the last time. I do see things more clearly, more indelibly, as I get older.

Why was it that you only started writing poetry a couple of years ago?

Yes, well that is a bit of a myth. I only started writing serious poetry in 1987. But I wrote my first volume of poetry when I was 11. And I sent it in to be reviewed. You could in those days you know — send it into a reviewers just to be reviewed — for a fee. I only submitted it when I was 17 or so, but I wrote it when I was 11.

What was the response?

He said ‘Well, one poem is very good, and the others are too personalised — you should rather forget about poetry.’ So I did. Also at that time (when I was 17) I wrote a novel. That took off very well and was published in England. So I decided I was a prose writer, not a poet. And then the war came. I wrote something in the Prisoner of War camps in indelible pencil and an old copy book which I got from the Red Cross. A psychedelic sort of prose that everybody said was absolutely marvellous stuff and I still think it was very marvellous myself.

Everybody? You mean, your fellow prisoners?

Yes, you know in Prisoner of War camps you have all kinds of intellectual guys there, artists and poets and what have you, very professional people. They thought it was great stuff. But then we moved to the other camp and the Germans took it and destroyed it in front of me. That devastated me and I didn’t write for years. When I became a Muslim in the 1960’s, I started to write religious poetry . . . but bad stuff, you know. I had no technique whatsoever. Well, that lasted for a long time. Then I was in prison in ‘87 and when I came out I wanted to express rage. Not faith or “crook a pinkie” stuff, I wanted now to express fury. I wrote a whole selection called Tormented which I submitted to various publishers. They said ‘Well, it’s very encouraging, but it’s not good enough.’ Which rather crushed me, but by that time I’d gained some resilience, because you know, hatred is a very motivating force.

I sent some of it to Douglas Reid Skinner at Upstream and he selected a couple of poems. And he wrote to me, he said ‘I’ll give you a few tips — when you want to stop saying something, put down a full stop, don’t carry on and on and on. And stop telling the reader what to think,’ he said, ‘let them think it out for themselves,’ all these kinds of things. I took all these to heart, and then I started to write in a completely different way, and then I took off.

So much for the Tatamkhulu myth . . . in fact, you’ve been writing all your life in various forms. On and off, yes. But only since ‘88, when I got some help, did I begin to write with any kind of technical soundness.

But still, when you did start writing poetry seriously, it seems your voice came out completely developed. You must have had an inner dialogue going for a long time for this to happen.

To be introspective (people equate this with reclusive) is to have a dialogue with one’s muse whether you like it or not. But the muse couldn’t use me because I didn’t have the technique to be used. The message I was getting was garbled.

How did you get it right?

I got it right because people helped me, told me where I was being old-fashioned, or crude, or naive, or whatever, and I rectified it, and the muse found it easier to speak through me. Well now we’re becoming real chommies.

Some questions about your life. You were born of Egyptian and Turkish parents, and they came out here when you were a baby.

Yes. They died when I was two years old.

Both of them? At the same time?

Yes, the flu epidemic of that time, remember? This was in the 20’s — I was born in 1920. Coming from Egypt I suppose that they were open to infection; one always is, when going to a strange country, I believe. I was adopted by a certain family, in the western Transvaal. I was given their name, brought up by them, in the Christian tradition, English-speaking people, 1820, settler stock. They used to read a lot. They were serious-minded people, quite intellectual.

Judging from your poems about your childhood it sounds like it wasn’t a happy family.

No, my foster mother and father fought like cat and dog. He was a horrible man.

How did you learn you were adopted?

They only told me as I was about to leave school. They said ‘Well you’re going out into the world now and we live in a difficult country’ — my foster mother actually told me — ‘a difficult country where race counts for a lot. Although you don’t look the part we’d better tell you that you’re not our son and your parents were Asian’ — as she put it. In those days, anybody who came from the Middle East was Asian, ‘coolie,’ she told me.

What was your reaction?

It was as though someone had dropped the bottom right out of my world. I felt rootless all of a sudden, lost, absolutely lost. But one gets out of these things when one is young. So I went on, using the same name, but always subconsciously aware of the fact that I was not what I was trying to be. It used to creep out in the oddest ways — the old ancestral blood. Like at school (this was before they told me) we had an art exhibition and I very carefully drew an Egyptian drawing, these one-sided figures of Egyptians. I got a five shilling prize at the agricultural show for that. Even from that early age I loved reading about Egypt.

And after school?

I became an articled clerk in an accounting firm for about 18 months. And then the war broke out. I joined the army to get out of being an articled clerk — man I hated it. I went to see a film at the time with this gung-ho stuff, the Indian frontier, a guy dies there beating a drum etc. I thought ‘This is for me, there’s a war, let’s go!’

I graduated at the South African Military College as an instructor in the permanent force, then I volunteered to go up north and went up with the Second South African Division, to Egypt. I was taken prisoner at Tobruk shortly afterwards and landed up in a Prisoner of War camp for three years.

War is the most unsettling experience. When I came back I didn’t have any ambitions at all, I just wanted to have a good time. I married and got divorced almost within months, fathered one son and got out of it as quickly as I could. I was too wild at that age, I had no sense of discipline whatsoever. I was forming boys’ clubs all over the place, you know, secret societies, getting into debt, launching out in the most insane ventures. I don’t drive a car but I was always buying cars and getting somebody else to drive them. Getting into debt, trading them in. I had no sense of responsibility at all. I think that’s why I landed up in what is now Namibia, sniffing adventure. Worked there on and off for twenty years, on the copper mines.

You settled down?

No. I didn’t have to worry about anything, I just had to do my shift. I had a band then. I was the manager of a band at the recreation club, and played on Saturday nights for the boys. That was all I was doing, nothing really constructive at all. It was only when I came to Cape Town in the 60’s, when I became Muslim, I began to realise there’s a bit more to life than this sort of thing.

How did you become Muslim?

I had been an atheist for quite a long time. I didn’t believe in anything. When I came to Cape Town I landed amongst Muslims more by accident than anything else. I couldn’t find work for about six months. I knew hell then, I knew what hunger was. The old woman who used to clean the baths and the toilets, we got talking, and we got very friendly and she said ‘You must come and visit my friends here in District Six.’ So one Saturday night I very fearfully walked up Hanover Street. It was like walking into a Cairo bazaar, a real lively place it was. I met up with this family and they took me to their hearts in an unbelievable fashion.

I heard the Qur’an being recited. Well, the Qur’an, you know, we Muslims believe is a miracle. Maybe some echo of it from childhood reverberated, but immediately I was attracted — I went and bought the Qur’an in English and read it for one whole week and became utterly convinced. So I went to my old friends here and said ‘I want to become a Muslim’ so they rushed me to the Sheikh and made me pronounce the faith, and I was a Muslim on the spot.

Then I began to think seriously about life and living. I concentrated deeply on religious matters — writing religious poetry and so on. Then I started up charitable work. I formed this organisation called Al-Jihaad. I still head it. I began to work in order to earn money to help the poor — people I am now writing about — and helping them, I became poor myself. Now at the age of 72, I have a very small salary, no hope of getting another job. I feel quite happy about it, at least I’ve wasted my money on a good cause.

How did you go from there to becoming a ‘terrorist’?

I started out in the political struggle in the early 80’s, under the banner of this religious organisation. Inevitably, working in close collaboration with other activists, I came into contact with ANC members, and into close contact with Umkhonto we Sizwe. I was later arrested for terrorism, we needn’t get into that. That’s where I got my name Tatamkhulu Afrika. It’s the only name that means anything to me. It’s under that name I flowered politically and also poetically. In any case the name I had before this wasn’t even my name at all.

Your prison experience was very important to you, more than the war, it seems.

Tremendously so. I would not have missed it for anything. The war did not have such an effect on me because it was a restricted experience. In a Prisoner of War camp you’re only meeting up with a small cross-section of humanity, but in prison you’re meeting up with a nation—with your own nation. Coming out of prison you were flowing out into an entire nation of oppressed people, which leads to a much wider and sharper reaction, a much greater absorption into people’s suffering and emotions. If I’d never gone to prison, I don’t think you’d be sitting here talking to me now, because I would not have written anything.

A small thing that happened in prison turned me completely around. Before I was in prison, we used to go to many funerals in the townships and we used to toyi-toyi. And there was one little black guy, a teenager, who was absolutely fascinated by this old man toyi-toyiing with the funeral processions. He’d always come and toyi-toyi with me all the way up to the cemetery, laughing like mad, you know, and slapping me on the back. A real joy to watch. The day we walked into prison, Victor Verster, we kicked up a stir. All the youngsters in prison were leaning out of the upper windows of the cells, watching us come in, us newcomers. And there was this kid, but he was completely changed. All the joy had gone out of him. He put up his hand like this, slowly, but there was no life left in him at all. I went to bed that night thinking of the way he used to be.

These youngsters used to toyi-toyi right through the night. I’ve never seen such energy—shouting slogans right through the night. And some of them who couldn’t take it any more used to scream hysterically. It was awful to listen to this. I think the suffering and the change in these youngsters broke my heart, to use a cliché. If one’s heart can break, it broke my heart, and I came out of there enraged.

You talk about being in the black section of the prison. Were you still classified white’ or had you somehow changed race classification?

I’ve never been classified ‘white.’ When I was in Namibia we were not classified at all. When I came down here in the 60’s, they wanted to classify me ‘white.’ I refused. I went into despair because I’d become a Muslim and I wanted to stay in District Six. In those days you were not allowed to stay in District Six as a ‘white’ person. I went to Helen Suzman and spoke to her about it and she said ‘I’ll help you.’ I gave her the names of certain people I knew from the days of my childhood. I don’t know what she did, whether she actually went and interviewed all these people, I haven’t a clue. But she called me in, about six months after that, to her office in Parliament, and told me that the Minister of the Interior had agreed to classify me ‘malay.’ So I became a ‘malay,’ although I’d never been a malay in my life. And she said ‘but now remember, whatever you do, don’t become visible, don’t take part in politics, for God’s sake, lie low.’ Well of course I didn’t heed her, in the early 80’s I ignored that completely.

What do you see as the challenge of political poetry in the 1990’s?

I’ve just written a paper for COSAW about this. What I’m saying there is that, after February 1990, it is still necessary to write political poetry. Political poetry in this new phase of the struggle — if you want to use the word ‘struggle’ — is a protest, not against political dominance but against dominance of wealth, of privilege, residual class barricades, which are very much there. It’s become even more necessary, because poverty and privilege are a greater menace to our society now than political dominance.

But we must write poetry which is poetry. It mustn’t be sloganising any more. It should never have been sloganising in the first place, unless it was an oral poetry from a political platform. There it played its role, it served its purpose. If we’re going to write poetry now, it must be good poetry. That of course is an old theme between the classicists and the new guys. I’m halfway between the two.

I’d like to be read by all people: by whites, privileged whites, people who could do so much to alleviate deprivation in this land and are not doing so; but also to be read by people who are poverty stricken that they might know, understand, that there are people who care. Whether it’ll help them in the long run, materially, I don’t believe. It might help them spiritually to some extent, and that’s about it.

You’ve said you write your poems in solitude in order to purge yourself, yet you find that you are striking a chord in a large group of people. It’s always like that when art comes from deep enough within the artist.

Well in writing to purge oneself — if one is doing it in a universal sense — one is purging others as well if you read it to them. After all, what I am concerned with at the moment — poverty and deprivation — is a universal thing. I myself do not live in the best of circumstances, I understand very well what poverty and deprivation is like. Whether I write in solitude or whether I don’t is really not the point. The point is that I know that what I am writing about will register with others who have shared this experience and it will get across to them.

You’ve spoken about the notion of the muse, the energy that shapes a poem. Is this a mystical experience, an ordinary experience, or both?

Well I believe absolutely that the muse exists, but what the muse is, I mean, who knows? Is it external? Is it internal? I don’t think it is really external because if it were external you would not develop a voice of your own. It is something that belongs to you. It will become operative if you encourage it to operate and it’ll die if you do not encourage it.

Sometimes one looks at a poem and thinks ‘Well — did I produce that?’ It just seems so unique, so not you, yet it is you. Only it is coming from an aspect of yourself which is alien to your normal self. I know some poets who say ‘you must wait for the muse to come to you.’ Well it’s nice if it does but it doesn’t always come to you that easily. I think that if you want to, you can induce it. I’ve done that, quite often. When I want to write and the muse is silent, I’ll grapple with it until I produce one line, one line which is musical, which begins to say what I want to say. I’ll write it down. I’ll dwell on that line until slowly another line is added and another and another — sometimes I don’t even know where I am going to. Anybody can be taught the rules of poetry, hey? But unless that person has a very strong muse, and encourages that muse, that person will never write lasting poetry.

Small round hard stones click

under my heels,

seeding grasses thrust

bearded seeds

into trouser cuffs, cans,

trodden on, crunch

in tall, purple-flowering,

amiable weeds.

District Six.

No board says it is:

but my feet know,

and my hands,

and the skin about my bones,

and the soft labouring of my lungs,

and the hot, white, inwards turning

anger of my eyes.

Brash with glass,

name flaring like a flag,

it squats

in the grass and weeds,

incipient Port Jackson trees:

new, up-market, haute cuisine,

guard at the gatepost,

whites only inn.

No sign says it is:

but we know where we belong.

I press my nose

to the clear panes, know,

before I see them, there will be

crushed ice white glass,

linen falls,

the single rose.

Down the road,

working man’s cafe sells

bunny chows.

Take it with you, eat

it at a plastic table’s top,

wipe your fingers on your jeans,

spit a little on the floor:

it’s in the bone.

I back from the

glass,

boy again,

leaving small mean O

of small mean mouth.

Hands burn

for a stone, a bomb,

to shiver down the glass.

Nothing’s changed.

TATAMKHULU ISMAIL AFRIKA

Leave a Reply