The purpose of this paper is to tell the story of Dr Muhammed Shukri Effendi, the first black medical student to graduate from UCT. Effendi, who studied at Trafalgar High School, went on to pursue his studies at the UCT medical school and graduated as a medical doctor in 1942. Previously, it was thought that Maramoothoo Samy-Padiachy, Cassim Saib and Ralph Lawrence were the first black medical doctors to graduate from UCT – in 1945.

This article is a summary of a forgotten prominent figure in the educational life of South African history. In spite of his active public life, Dr Muhammad Shukri Effendi has been overlooked by historians.i

Muhammad Shukri Effendi was the first Muslim medical doctor who qualified at the medical school of the University of Cape Town in 1942. He was classified as a non-European and non-white citizen; as such, it was a difficult challenge for him to study in South Africa, especially given the limited educational opportunities and financial aid for non-whites at that time. In order to better understand the educational struggles for non-whites citizens, one must delve into the extent to which race was an obstacle. According to colonial understanding, Apartheid, as a concept, existed even before Afrikaners came to power in 1948 but it was not institutionalized. It was more racial prejudice not so much based on skin colour but class and religious beliefs. Even before apartheid there were schools for only English speaking or Afrikaans speaking whites. The Afrikaans which the Cape Malays and Coloured communities spoke was not the same as that spoken by the white Afrikaners. Therefore, while Dr. Shukri Effendi was only accepted to Trafalgar High School which was established by a coloured intellectual Dr. Abdullah Abdurrahman, another Turkish student who was Christian, Reginald Remzi, was easily accepted to SACS High School which was regarded as one of the most popular white schools at the Cape.ii

Non-white individuals’ social situation and their lifestyle were determined by the white government’s rules even before the apartheid regime. For instance, in 1919, there was a period of intense Afrikaner nationalism, and the idea of racial segregation of Afrikaners, English, and Black residents of South Africa was promoted. White and non-whites were plunged into extreme poverty, but the government focused on alleviating the plight of Whites while ignoring Black suffering. Increasing numbers of non-European people moved to urban areas in a bid to survive and pass laws were strictly enforced. Furthermore, non- white families began migrating to cities as a result of increased job opportunities and the grinding poverty they were experiencing in rural reserves created for them through the 1913 Land Act.

Morrow states that:

The history of African education in South Africa from colonial times to the Apartheid Era had much in common with the history of colonial and post-colonial education in Africa. In both contexts there was a constant emphasis on the need for special attention to be given to the education of rural peoples and the orientation of the curriculum to the needs of rural societies.

Despite these difficulties, Mohammed Shukri was registered as a student in Medical School at the University of Cape Town in 1935. He specialized as a medical doctor and became an intellectual in the South African public sphere. In spite of being the first non-white medical doctor at the University of Cape Town, he became a forgotten character in South African history. Likewise, his cousin, Doctor Havva Khairunnisa, was forgotten despite being the first Muslim woman doctor in South Africa. These forgotten figures in South African history will be analysed in the light of archival sources in this study.iii

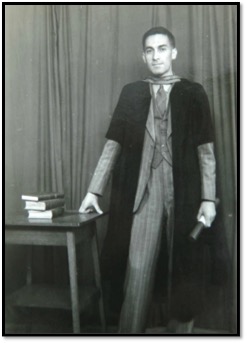

Dr. Mohammed Shukri Effendi

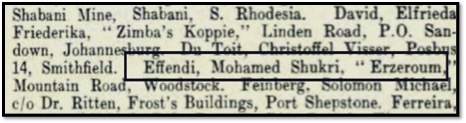

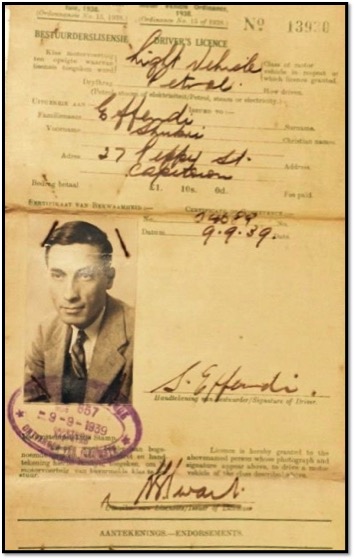

Mohammed Shukri was born in Pepper Street in the Bo-Kaap, a well-known Muslim quarter in Cape Town, on December 8, 1915. His father was Omar Jalaleddin Effendi, who was of Turkish descent. Mohammed Shukri’s grandfather, Abu Bakr Effendi, was an erudite Muslim theologian sent to South Africa from Istanbul to educate Muslims at the Cape of Good Hope in 1862. Mohammed Shukri’s mother was a Cape Malay Muslim woman, Amina, who had eight children, named Fouzi, Hussain Nuri, Muhammad Shukri, Ahmad Shakir, Tyra, Nabia, Fatima, Adela. However, after a while, they moved to Mountain Road, Woodstock. A possible reason for them moving was that the Bo-Kaap house became too small for all the children. The house in Woodstock was registered as a stony house, “Erzurum”, which is the name of home city of Muhammad Shukri’s grandfather, Abu Bakr Effendi, in Turkey.iv

Mohammed Shukri attended Trafalgar High School in Cape Town. Trafalgar High School is a secondary school in District Six in Cape Town, South Africa. It was the first school built in Cape Town for coloured and black students. Famous South African politician Dr. Abdullah Abdurrahman established Trafalgar High school and his daughter Zainunnisa Cissie Gool also attended that school during the same years as Mohammed Shukri. Dr. Mohammed Shukri’s uncle, Ahmet Attaullah Bey, was married to Muhsine, who was the sister of Dr. Abdullah Abdurrahman. This also helps indicate that Shukri Effendi was regarded as coloured and classified as non-European in South Africa because of his religion. In his registration papers at the medical school, his home language was recorded as English– Afrikaans was recorded as the second language. However, it is rumoured that they all spoke Afrikaans at home. The reason he wrote down English was that at that time, and even today, UCT is an English-medium University. In his registration form for admission to UCT, he was recorded as Muslim, Malay.

In spite of the remarkable substantial evidence above, Dr. Mohammed Shukri has not been mentioned in the history of South Africa. The Effendi family was classified as Malay Muslims or Muhammadan which was accepted as a lower class, not because of their skin colour, but because of their religion. Although skin colour has been seen as the determining factor separating the people in Apartheid Era, Muslims have always been regarded as secondary citizen in society, like Indian or coloured people. Therefore, it would seem unlikely that Shukri Effendi might have gotten admission at UCT. However, Shukri Effendi might have been confused for a white man because his grandfather Abu Bakr Effendi was of Turkish origin and was accepted as a white citizen in colonial Cape Town. His grandmother Tahoora Effendi was of English descent and was also regarded as white in the 19th century. Dr. Shukri’s father, Omar Jalaleddin Effendi also had a white skin, but was married to a foreigner Muslim Lebanese woman Maryam. So, in terms of skin colour, they were all white people, but the religious practices played a constitutive role in their life leading them to be regarded as of a lower class than “European”. Like other members of the Effendi family, Shukri Effendi was a Muslim man and therefore he was also regarded as Malay. However, he looked like a white gentleman which might have played an important role in his educational life in South Africa. The other reason was probably his well-known family roots which go back to Turkey. Mohammed Shukri’s uncle, Ahmed Attaullah Bey was the first Muslim politician in South Africa. His uncle was married to Muhsine who was the elder sister of Dr. Abdullah Abdurrahman. His other uncle Hesham Nimetullah Effendi was the chairman of the Muslim Association in Cape Town and had a doctoral degree in Islamic science.v

These factors must have played a crucial role in his educational life while he was studying in medical school at UCT. According to Phillips, “UCT opened the clinical years of the M.B,Ch.B course to Coloured students for the first time in 1943”, however in practice it was not that much strict or this was an exceptional situation. For instance, Ralph Lawrence had been accepted to study medicine at UCT in 1940 and more importantly, Mohammed Shukri Effendi studied earlier than this time.

When Anne Digby wrote about the Earliest Black doctors in South Africa, she might have confused the ethnic identity of the members of the Effendi family in South Africa. Professor Digby states that.

In 1945 Maramothoo Samy- Padiachy, Cassim H. Said and Ralph A. A. Lawrence were the first black medical students to graduate from Cape Town. Lawrence was among the first black medics to graduate from UCT in 1945, along with Maramoothoo Samy-Padiachy and Cassim Saib.vi

However archival sources provide information that challenges this statement. According to the administration archives at the medical school of UCT, another black medical student studied at medical school at UCT between 1935 and 1941, qualifying as a medical doctor in Cape Town. Dr. Mohammed Shukri Effendi in fact studied much earlier than the other students Digby mentions in her article. According to Dr. Shukri Effendi’s registration form, in 1941 he qualified as a medical doctor, specializing as a doctor, and graduated in February 1942. He worked at Groote Schuur Hospital for a while and then opened his own practice in his office in Bo-Kaap. According to the South African Medical Journal Dr. Shukri moved his practice to Woodstock in 1946.

It is also possible that Digby confused the ethnic identity of Dr Shukri Effendi because his ancestral roots go back to Turkey. In Dr. Shukri Effendi’s birth certificate, his father was recorded as Turkish and his mother as Muhammad (Muslim) and that would make him non-white at that time in South Africa. Dr. Shukri Effendi’s father, Omar Jelaleddin Effendi was also born in Cape Town from a Turkish father, Abu Bakr Effendi and Muslim mother Tahora Saban Cook. His national identity might have caused a misunderstanding about his racial status in South African society.vii

However, in this context, there is another instance that would explain how the ethnic segregation was in South African society. In the same years, another Turkish student studied at medical school at the University of Cape Town and qualified as a medical doctor two years earlier than Mohammed Shukri Effendi. Dr. Reginald Remzi Bey was the son of the first official Turkish consulate of South Africa. His father was Mehmet Remzi Bey who came to South Africa. Despite his Turkish roots, Dr. Reginald was classified as white because of the religion he chose. Probably as a result of his mother’s influence, he became a Christian and took the name Reginald.viii

When Reginald was studying at University of Cape Town, Mohammed Shukri was also a student in the same department. However, due to religious differences, they were classified in different ways in South Africa. This is because while Shukri Effendi went to Trafalgar High School, Reginald completed his high school degree in SACS high school in Newlands. This indicates that being Turkish did not mean necessarily determine the ethnic identity of Turkish people as white or non-white, and that the religious factor was more important for segregation of nations in the context of the history of South Africa. Therefore, it can be said that Dr. M. Shukri Effendi’s religious identity might have been overlooked by scholars, but his national identity might be caused a misunderstanding in South African Society.ix

Mohammed Shukri Effendi died at the young age of 30 and was buried at the Mowbray Cemetery in Cape Town. His early death might also have contributed to his obscurity in the historical records of South Africa.x This is relevant in the context of apartheid in South Africa when, prior to 1943, universities were subject to strict laws of racial segregation and did not allow non-whites to study at UCT. The classification of the present generation of the Effendi family puts the historical matter into context. A copy of the ID of a living member of the Effendi family, Hesham Nimetullah Effendi, clearly shows he is regarded as a Cape Coloured despite his fair skin colour.xi

Conclusion

This study aims to expose this neglected family in South African history, the Effendis, who have consistently produced intellectual figures in South African society. Firstly, an erudite theologian, professor of divinity Abu Bakr Effendi, came to South Africa from Istanbul to educate Muslims at the Cape in the second half of the nineteenth century. He left a tremendous cultural legacy in South Africa and passed away in 1880. One of his sons, Ahmet Attaullah became the first Muslim politician of South Africa; and in turn it was Ahmet Attaullah’s daughter Havva Khayrunnisa, who was the first Muslim woman doctor in South African history in 1920s. Likewise it was her cousin, Dr. Mohammed Shukri Effendi, who went to the medical college of the University of Cape Town in 1935 and qualified as the first Muslim medical doctor in 1941 at UCT. In spite of the remarkable educational background of the members of the Effendi family, knowingly or unknowingly, prominent figures among the Effendis have been ignored or neglected by South African scholars. These omissions caused misconceptions in South African historiography. Thus far, in one way or another, a number of Effendi family members have been overlooked by scholars, however, archival documents and local newspapers provide substantial documents confirming the significance of this family in the history of South Africa. Dr. Mohammed Shukri Effendi was a member of this educated family, and like his predecessors in his ancestral history, he also studied well in spite of the difficult circumstances of Muslims at the time of the segregation of the non-white community in South Africa.

Notes

i Gencoglu, Halim. 2015. “Two forgotten medical doctors: Mohammed Shukri and Havva Khayrunnisa Effendi”. Quarterly Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa. 69 (1): 52-57.

ii Cape Town Archives Repository, 3/CT 4/2/1/3/1351 B605 Re: Additions to Premises “Erzeroum” Mountain Road, Woodstock. 1946. After 1948, this side of Effendi family claimed to be re-classified as white by the Apartheid Government, on condition that they replaced their name with Christian however Shukri Effendi’s family did not accept this offer and moved to Turkey. See, Gençoĝlu Halim, 2000 Güney Afrika’da Osmanlɪ İzleri, p. 300, Tezkire Yay. İstanbul.

iii Howard, Phillips, 1993 The History of UCT, p 216, See also, http://www.uct.ac.za/dailynews/?id=7226 Faculty News of Health Science, January 2010 the Faculty Remembers Ralph Lawrence pp.1 University of Cape town: Digby, Anne, 2005, Early Black Doctors in South Africa, The Journal of African History, Volume 46, Issue, 03, November, DOI: 10.1017/S0021853705000836, pp 437:.A Medical Journal, July 27 1946 p. 427 Muhammad Shukri Effendi was Muslim student and therefore being non-white, he went to Trafalgar High School in District in Cape Town. This factor made him technically non-white even he has a white Turkish appearance.

iv Cape Archive, Mooc, 6/9/13178 4322/46 Effendi, Mohamed Shukri Estate Papers. 1946.

v Digby, Anne, 2005, Early Black Doctors in South Africa, The Journal of African History. p. 437, Volume 46, Issue 03 November, DOI: 10.1017/S0021853705000836. Muhammad Shukri Effendi was Muslim student and therefore being non-white, he went to Trafalgar High School in District in Cape Town. This factor made him technically non-white even he has a white Turkish appearance.

vi Digby Anne, 2005 The Earliest Black Doctor in South Africa 1883- 1913, p.3.

vii Digby, Anne, 2005, Early Black Doctors in South Africa, The Journal of African History / Volume 46 / Issue 03 / November, DOI: 10.1017/S0021853705000836, pp 449.

viii Scholar’s search uncovers UCT’s first black medical doctor, https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2016-04-12-scholars-search-uncovers-ucts-first-black-medical-doctor, accessed 08. 12. 2021.

ix South African National Archive, GG 1192 28/599 Enquiry regarding the present circumstances of Madam Helena Remzi Bey and her two children 1928.

x Çolak Gűldane, 2013, Avrupada Osmanlı… pp. 71-73

xi Gençoğlu, Halim. 2020. Ottoman cultural heritage in South Africa: Islamic legacy of the Ottoman Empire at the tip of Africa (archival records, photos and documents) = Güney Afrika’da Osmanlı kültürel mirası: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Afrika’nın ucundaki Islam mirası (arşiv kayıtları, resimler ve belgeler). Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu, Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları.

Leave a Reply