For almost a century and a half France maintained a substantial colonial empire in Africa, stretching from the Maghreb through the Western and Central sub-Saharan regions. Though direct rule ended in the early 1960’s, French influence over its former possessions continued. Through political, economic, and cultural connections, France has attempted to maintain a hegemonic foothold in Francophone Africa, both to serve its interests and maintain a last bastion of prestige associated with a legacy of past mastery. However, do these relations retain an essentially colonialist character? To determine this, we shall first briefly analyse the main rationale behind France’s imperial expansion; its ‘mission to civilise’. We shall then explore France’s more recent and existing relationships with its former possessions and conclude.

French legacy in Africa

General information on French colonial rule in Africa can be found in works dealing with French imperialism as a whole, in specific regional or national histories, as well as in general and comparative studies of European colonialism in Africa.i

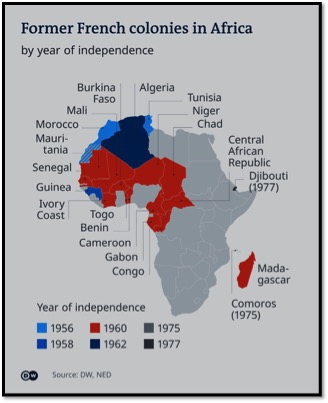

French presence in Africa dates to the 17th century, but the main period of colonial expansion came in the 19th century with the invasion of Ottoman Algiers in 1830, conquests in West and Equatorial Africa during the so-called scramble for Africa and the establishment of protectorates in Tunisia and Morocco in the decades before the First World War.ii To these were added parts of German Togo and Cameroon, assigned to France as League of Nations mandates after the war. By 1930, French colonial Africa encompassed the vast confederations of French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa, the western Maghreb, the Indian Ocean islands of Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros, and Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. Within this African empire, territories in sub-Saharan Africa were treated primarily as colonies to exploit, while a settler colonial model guided colonization efforts in the Maghreb, although only Algeria drew European immigrants. Throughout Africa, French rule was characterized by sharp contradictions between a rhetorical commitment to the “civilization” of indigenous people through cultural, political, and economic reform, and the harsh realities of violent conquest, economic exploitation, legal inequality, and sociocultural disruption. At the same time, French domination was never as complete as the solid blue swathes on maps of “Greater France” would suggest.iii As in all empires, colonized people throughout French Africa developed strategies to resist or evade French authority or co-opt the so-called civilizing mission, and cope with the upheavals of occupation. After the First World War, new and more organized forms of contestation emerged, as Western-educated reformers, nationalists, and trade unions pressed by a variety of means for a more equitable distribution of political and administrative power. Frustrated in the interwar period, these demands for change spurred the process of decolonization after the Second World War. Efforts by French authorities and some African leaders to replace imperial rule with a federal organization failed, and following a 1958 constitutional referendum, almost all French territories in sub-Saharan Africa claimed their independence. In North Africa, Tunisian and Moroccan nationalists were able to force the French to negotiate independence in the 1950s, but decolonization in Algeria, with its million European settlers, came only after a protracted and brutal war that left deep scars in both postcolonial states. Although formal French rule in Africa had ended by 1962, the ties it forged continue to shape relations between France and its former colonial territories throughout the continent.iv

French influence in African politics over the past few decades

France has good cause to seek to improve its image in Africa. Resentment has built-up due to political interference and armed interventions, not least the legacy of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. French forces facilitated the training and expansion of the Forces Armées Rwandaises from 1990 to 1993 and provided huge shipments of arms.v Though stabilisation was the chief motivation, France effectively if unwittingly helped militarise Rwanda prior to a pre-planned massacre. Shock at these events and a growing chorus of humanitarian advocacy in French civil society have led to recent governments reforming the terms of their African military cooperation and engagements, as noted above.vi France has been amicable to certain withdrawals, such as the pull-out of 1200 troops and transfer of base sovereignty to Senegal in 2010, yet still retains the will and capacity to intervene, as demonstrated in Ivory Coast when French forces, long in-theatre under Force Licorne, assisted in overthrowing Laurent Gbagbo– albeit with UN endorsement.vii

Ultimately France has successfully used its security presence since decolonisation to exert influence in countries where it has interests, maintaining both regional hegemony and its vision of order and stability. While that strength is still potent, strategic rationales for maintaining substantial presences are weakening and, in addition to wary French and African public opinion, recent initiatives by the African Union also threaten to further weaken France’s interventionist reflex, such as the 2004 creation of the Peace and Security Council and its African Standby Force to (supposedly) allow Africans to handle their own affairs.viii France also has a considerable military presence in Africa. It leads the Barkhane operation against Islamist groups in the Sahel region, in which around 5,100 soldiers from several countries are involved. According to the US daily “New York Times”, in 2007, almost half of France’s 12,000 peacekeeping troops were deployed to Africa. These troops have both military and advisory capabilities as well as supporting and stabilizing the regimes of the respective countries.

Within a twenty-year period, France’s African colonies passed from its control, though Charles de Gaulle still perceived ‘that French world power and French power in Africa were inextricably linked and mutually confirming’.ix Though De Gaulle’s Communauté Franco-Africaine tried to keep the system intact – not least through threatening to sever French support, as a dissenting Guinea discovered to its cost – the African colonies, already used to de facto if not de jure sovereignty thanks to Defferre’s Framework Law rapidly declared independence.x Though a dazed France largely accepted this, we are seeing early initiatives to maintain ties with former colonies through economic and security agreements, and it could be argued that the breakup of the colonial federations into their constituent states made them more reliant on France than they would have been if unified. ‘‘Decolonisation did not mark an end, but rather a restructuring of the imperial relationship’’ and we see this in Françafrique; the political, security, economic and cultural relations that, though diminished somewhat, remain today.xi Additionally, “60 years on, francophone countries in Africa still do not have true independence and freedom from France,” says Nathalie Yamb, adviser to Ivory Coast’s Freedom and Democracy Party. “Even the content of school textbooks is often still determined by France,” she added. But more importantly, the political system in many of the countries was introduced by France. “Shortly before independence, France decided to abolish the parliamentary system in some countries like Ivory Coast and introduce a presidential regime in which all territories and powers are in the hands of the head of state,” Yamb told DW. The reason being that in this way, “only one person with all the power needs to be manipulated”. Françafrique, as French influence in the former colonies is called, remains a fact, particularly galling to the young, whose resentment of the former colonial power is growing.xii Beginning in the 1980s, many French presidential candidates have been announcing plans to put an end to Françafrique. But the promise of a new beginning between France and the francophone states has turned into a mere ritual, according to Ian Taylor, professor of African politics at St. Andrews University in Scotland. “They come out with statements, and they want to change it. But after a couple of years, they realize that the business interests and the kind of political interests are still very strong and there’s no real will on either side to fundamentally re-balance the relationship,” Taylor said.xiii

A coup in another French colonized country: Guinea

Left unchanged, at least for now, however, are African commitments like these that date to independence 36 years ago. Besides Gabon, French troops are based in the Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Senegal, Central African Republic, Chad, Djibouti and the Indian Ocean islands of Reunion and Mayotte. In addition to the countries where it has troops, France has military cooperation agreements with Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, Togo, Equatorial Guinea, Congo, Zaire, Rwanda and Burundi.xiv The scepticism turned to derision when Niger’s first democratically elected Government fell to a military coup in February. At the time, France, which has a defense treaty with Niger, said it regretted the development but would not intervene. Same threat is happening in other African countries like Guinea.xv

On September 5, the President of Guinea Alpha Conde was captured by the country’s armed forces in a coup d’état after gunfire in the capital, Conakry. Special forces commander Mamady Doumbouya released a broadcast on state television announcing the dissolution of the constitution and government. After several decades of authoritarian rule in Guinea, Condé was the country’s first democratically elected leader. During his time in office, Guinea used its rich natural resources to improve the economy, but the bulk of the country’s population has not felt its effects. In 2020, Condé changed the constitution by referendum to allow himself to secure a third term, a controversial change which spurred the 2019 -2020 Guinean protests. During the last year of the second term and his third term, Condé cracked down on protests and on opposition candidates, some of whom died in prison, while the government struggled to contain price increases in basic commodities. In August 2021, in an attempt to balance the budget, Guinea announced tax hikes, slashed spending on the police and the military, and increased funding for the office of the President and National Assembly.xvi

The coup began in the morning of September 5, when the Republic of Guinea Armed Forces surrounded Sekhoutoureah Presidential Palace and cordoned off the wider government district. After a shootout with pro-government forces, the mutineers, who appear to be led by Doumbouya, took Condé hostage, announced the dissolution of the government and its institutions, annulled the constitution, and sealed off the borders. While local politicians have not explicitly opposed or supported the coup, the takeover was met with almost universal disapproval of foreign countries, which have called for the coup to stop, for the prisoners to be released and for constitutional order to return. Guinea possesses over four billion tons of untapped high-grade iron ore, a third of the world’s bauxite reserves which are used to make aluminium, undetermined amounts of uranium, manganese, nickel, significant gold and diamond reserves, and prospective oil reserves. The West African country of Guinea is rich in natural resources, but years of unrest and mismanagement mean it is one of the world’s poorest countries. It seems that Guinea’s coup exposes the scramble for resources in the region.xvii

Conclusion

The main goal of colonizing West Africa was to turn West African countries into a “French-state”. This means changing their way of living, making the official language French, and making them convert to Christianity. French colonization changed African culture but today France’s army keeps its grip on African ex-colonies. After 150 years of French colonization of CAR (Central African Republic) there was only one person with a doctoral degree when the country became independent in 1960.

Most French colonies in Africa are still under French rule and culture of assimilation. Their stooges are the kings of the ‘democratic’ dictatorship, which is why these people are fleeing their homes. Similarly, 14 African countries are still forced by France to pay colonial tax for the benefits of Slavery & Colonization: 80% of the 10 countries with the lowest literacy rates in the world among adults are in francophone Africa. France continues to collect rent on the colonial buildings they have left in these countries. It is estimated that these African countries pay over $500 Billion as colonial tax to France each year. In short, until France leaves Africa, economic hegemony and coups will continue.

Notes

i Gençoğlu, Halim. 2020. Türk arşiv kaynaklarında Türkiye – Afrika, Turkey – Africa in the Turkish Archival Sources. İstanbul, SR Yayınevi.

ii Cook, Steven A. 2007. Ruling but not governing: the military and political development in Egypt, Algeria, and Turkey. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

iii McDougall, James. 2017. A history of Algeria. New York: Cambridge University Press,

iv Ruedy, John. 2005. Modern Algeria: the origins and development of a nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

v McNulty 2000, pp. 109–110.

vi Allman, Jean Marie, Susan Geiger, and Nakanyike Musisi. 2002. Women in African colonial histories. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

vii Chafer, Tony. 2002. The end of empire in French West Africa: France’s successful decolonization? Oxford: Berg.

viii Williams 2009, p.614.

ix Charbonneau 2008, p.281.

x Shipway 2008, p.20-21

xi Chafer cited in Charbonneau 2008, p.281

xii Holder Rich, Cynthia. 2011. Indigenous Christianity in Madagascar: the power to heal in community. New York: Peter Lang.

xiii Diakité, Penda, and Baba Wagué Diakité. 2006. I lost my tooth in Africa. New York: Scholastic Press.

xiv Since its 1964 intervention in Gabon, France has intervened militarily on the continent every other year on average. Paris has repeatedly sent troops into action in Chad, flown in paratroopers to rescue French and Belgian nationals in Zaire and help put down an insurrection there, and used its forces to replace political leaders in the Central African Republic. See, Arnold, Guy. 2008. Historical dictionary of civil wars in Africa. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press.

xv Luckham, Robin. 1982. “French Militarism in Africa”. Review of African Political Economy. (24): 55-84.

xvi Guinea coup attempt: Soldiers claim to seize power from Alpha Condé, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-58453778, accessed 4 September 2021.

xvii Gilbert M Khadiagala, Fritz Nganje. (2016) The evolution of South Africa’s democracy promotion in Africa: from idealism to pragmatism. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 29:4, pages 1561-1581.

Leave a Reply