The domestic political situation in Mali is only getting worse: the country is split, political elites oriented towards France are no longer satisfied with the population, leaders of different groups offer varying alternatives. For those unfamiliar, UWI covered the general situation in an earlier article.

The Great Anti-French Revolution in Mali: Françafrique Fails

Against this background, it is interesting that the economic organization ECOWAS (The Economic Community of West African States), stood up for the President of Mali and did not support the removal of Ibrahim Boubacar Keita from his post.

A virtual emergency summit on the social and political situation in Mali is scheduled for July 27. This is taking place immediately after ECOWAS leaders met in Bamako, the capital of Mali.

It will be recalled that regional leaders, which included the Chair of the Authority of Heads of State and Government of ECOWAS and President Mahamadou Issoufou of Niger, and President Mohamedou Boukhari, met with President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita of Mali in response to growing political unrest.

Destabilization in Mali

Mali has been protesting for months, with demonstrators calling on the President to resign. They began on June 5, when those disgruntled with Keita’s power gathered in the streets of Bamako. The first large-scale demonstration against the president gathered on June 19.

There were many claims: economic collapse, problems with Islamists, tribal strife, corruption and France-oriented elites. The last straw was the elections, which many protesters see as having been rigged.

President Keita is a pro-French president, and he makes no secret of it. He negotiates with Macron and various Western international structures; he’s also trying to preserve his image as a secular leader. However, perhaps as a result, he has been unable to maintain the people’s trust – the final demand of the protesters is Keita’s resignation.

ECOWAS has already intervened here, opposing Keita’s resignation (he is, after all, a convenient and manageable leader). The organization’s leaders said that a political vacuum could exacerbate the internal chaos and tried to convey to the Malians that they would press Keita to quickly deliver on his promises to the opposition, hoping to persuade the opposition to accept the offer.

But the opposition refuses to talk to the president and demands his immediate resignation. As we wrote earlier, international “peacekeepers” even tried to get in touch with the leader of the Movement on June 5, such as Mahmoud Dicko – Movement of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP). Apparently, they did not reach consensus, as Dicko himself now insists on the president’s resignation.

Called the “People’s Imam”, Dicko last year mobilized tens of thousands of people to force the Prime Minister of Mali to leave. He is now one of the most popular opposition leaders. At the same time, he does not offer himself as a leader, and this modesty adds to his charm among the local, predominantly Muslim population.

On the structure and objectives of ECOWAS

What is the structure of ECOWAS today, and why does the organization have the authority to act in the internal policies of individual countries?

ECOWAS is a regional political and economic union of fifteen countries located in West Africa including Benin, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

It was founded in 1975.

Considered to be one of the main regional blocs of the continental African Economic Community, the ECOWAS’s stated goal is to achieve “collective self-reliance” of its member States.

The organization comprises two economic-oriented clusters:

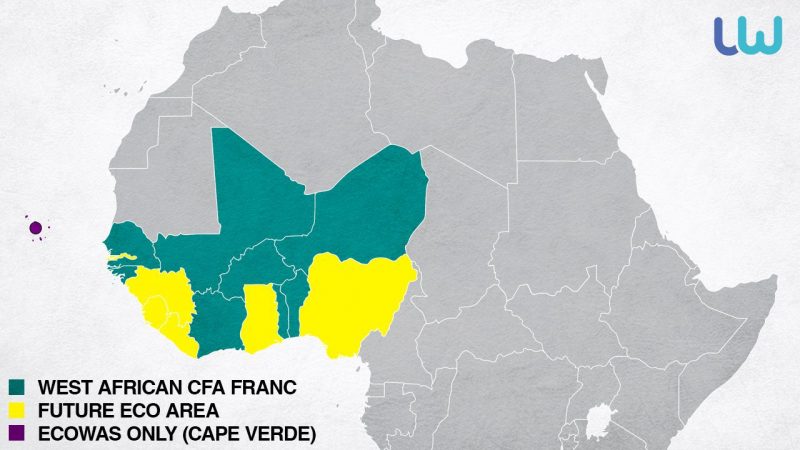

– the West African Economic and Monetary Union (also known by the French acronym UEMOA) is an organization composed of eight, mostly French-speaking, ECOWAS States that share a common customs union and monetary union.

– the West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ)

The Conference of Heads of State and Government is the supreme governing body. ECOWAS also has a Parliament, a Court, an Ecobank, an Economic and Social Council, commissions (on trade, customs policy, etc.).

Among the stated objectives of ECOWAS are the fight against poverty, the establishment of transport and energy infrastructure, arms control (a moratorium on the import, export and manufacture of small arms), maritime and fishing infrastructure, the control of tourist checks, and (potentially) the introduction of a single “eco” currency in the region.

But the most interesting thing is the abstract maintenance of peace and security in “hot spots” (the most striking examples are Liberia, Guinea-Bissau and Mali), the fight against crime and smuggling. This last point goes beyond a purely economic settlement and allows the organization (with the help of French structures) to interfere in the internal affairs of individual states.

The organization has been criticized for other reasons as well. Having existed since 1975, it has so far been unable to provide rail links between Nigeria, which has recently been Africa’s largest economy, and the rest of ECOWAS countries, and has been unable to develop effective payment systems and customs regulations.

At the same time, ECOWAS would have to ensure that its members meet a fiscal deficit of no more than 4% of GDP, which is almost impossible for many of the countries involved.

All this, in addition to poverty, is accompanied by internal political and ethnic instability in several member countries.

The “Eco”: the currency of discord

The currency issue is a separate and perhaps the most important criticism of ECOWAS, which explains the organization’s attempts to interfere in the affairs of its member countries.

For many years now, the organization has been trying to introduce an “eco” by replacing the CFA franc, which (in real and symbolic terms) represents French financial neocolonialism in Africa.

Failure Francafrique: why France is losing influence in Africa

The initiative, according to ECOWAS members, is being introduced precisely to “decolonize” and free Africa, making it independent of France.

But which country has become the main mediator in the currency transition and is responsible for implementation? That’s right, France!

The new currency is not a liberation of Africa, but, at best, just a name change. At worst, it is also a more convenient control over Africa.

The question then arises: why is the African initiative being taken not so much by the Nadafican structures as by Paris yet again? And how will “eco” be anchored?

The answer is also inconvenient for ECOWAS enthusiasts: the Bank of France will continue to guarantee currency parity against the euro, while the currency itself will be directly linked to the European Central Bank.

Recall that the CFA zones (West African in eight countries and Central African in the other six) cover at least 12% of the GDP of the continent, which is home to over 150 million people. Naturally, Europeans do not want to give financial sovereignty and a chance for independence to such a tidbit.

Pan-African activists, like Kemi Seba, clearly see this as a continuation of neocolonial politics.

“Eco is a lure, a real bait that will further impoverish the population, in this monetary neo-colonialism”, Le Matin Libre said quoting Seba.

“As a condition for the implementation of the Eco, it was necessary to be in a process of being able to respect the convergence criteria, which are a deficit of 3% of GDP; and this is where France-Africa has been extremely strategic, as it knew that the Uemoa countries were the ones that were closer to the convergence rate criteria. France-Africa bet on the fact that since the countries of the Franc zone were the closest to this convergence rate, they would be the first to enter into the application of the Eco. In doing so, they said that the first to use the Eco would be the first to be responsible for guiding the Eco’s monetary policy. The strategy of the Uemoa countries is not to make the Eco disappear. These African dictators never had the objective of abandoning the Fcfa. Uemoa’s strategy is not to abandon the Fcfa for a new Eco currency. Their real objective is to extend the Uemoa Zone to all the other West African countries that have their national currencies. They want an enlarged Franc Zone, while the African populations want the Fcfa to disappear”, he argued. Faced with this, Seba does not intend to give up. He is planning a big mobilization for September 14 in several countries, inviting all those who inclined to resist against this state of affairs. “We are not people who reject the idea of a single currency, but we will not accept the use of a currency to ruin ourselves and our populations even more,” he suggested.

In his assessment, Françafric is not going anywhere because of the “eco”: French military bases and giant companies remain. Whatever the name of the currency, it is the French who remain the beneficiaries of Africa’s resource wealth. At the same time, Seba adds, at least a referendum should be held on this issue, instead of being a choice made by elites.

Changing the name of the currency would play no positive role, given that the countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA/WAEMU) have already concluded a collective foreign trade treaty within the WTO. With such a heavy dependence on foreign financial injections, the currency sovereignty of the region is out of the question. As the Senegalese economist and writer Ndongo Samba Silla said, “Eco” sounds like a death sentence for the CFA: “No, the CFA franc is not dead. Macron and Ouattara were only spared the polemical splendour”.

Avec "leurs" réformes, #Macron et #Ouattara ont signé l'acte de décès du projet d'intégration monétaire entre les 15 pays de la CEDEAO.

— Ndongo Samba Sylla/nssylla.bsky.social (@nssylla) December 21, 2019

Another Senegalese economist, Felvin Sarra, recalled that the measure is completely strange without the participation of Nigeria, the dominant demographic and economic power in the region. “We might as well save money and stop distracting people with contradictory statements,” he said.

In summary, the monetary zone without fiscal federalism is doomed to failure. The creation of a single currency without a common economic, employment and social policy could do much harm to African countries. Each country needs reforms before a new currency can emerge.

African Continental Free Trade Area

ECOWAS is overseeing one important project that UWI covered earlier, the African Continental Free Trade Area.

African Continental Free Trade Area: hope or neo-colonialism?

On July 21, 2020, the Economic Community of West African States held a virtual meeting on the African continental free trade area.

AfCFTA aims to create a single continental market for goods and services with free movement of business people and investment to accelerate and establish a continental Customs union.

The objective of the workshop is “to improve our understanding of the AfCFTA within ECOWAS so that ECOWAS institutions and specialized agencies can contribute more effectively to the negotiation and implementation of the Agreement.” Optimists believe that this will lead to increased trade in the region and on the continent. The pessimists believe that this will only be a more convenient mechanism for ECOWAS to reverse the situation in front of external colonizers.

In any case, AfCFTA will bring together 55 African countries with a total population of $1.2 billion and a combined GDP of more than $3.4 trillion – these are very high stakes, and ECOWAS cannot stand to lose control of convenient presidents in the region.

ECOWAS and military measures

As we noted above, ECOWAS also claims to be involved in regional military conflict resolution. The ECOWAS Treaty, as revised on July 24, 1993, granted the organization supranational status in accordance with article 58, paragraph 2, of the Treaty. However, the experts note that this does not give ECOWAS the authority to replace sovereign States.

For example, article 3 (d) of the 1999 ECOWAS protocol examines measures to be taken in the areas of conflict prevention, peacekeeping operations, combating cross-border crime, international terrorism and the proliferation of light weapons and anti-personnel mines. In that context, an “early warning” mechanism had been established. It included a surveillance and monitoring centre where data were collected.

Regional armies are being established through those centres to intervene in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire.

But in fact, as practice shows, ECOWAS is useless in addressing regional conflicts. The case of Mali is no exception.

The role of ECOWAS in the Malian crisis was initially ambiguous, because it failed to regulate relations of two conflicting Tuareg groups, Ansar Dine and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, even though the two movements did not have the same objectives. While the former preferred to apply Sharia law, the latter claimed autonomy, MaliWeb notes. However, these efforts have not led to anything, the Islamist uprising has achieved such success that the Malian government has invited French troops to the country.

In other words, as a result of the ECOWAS measure to resolve the armed conflicts ripping up the Sahara and the Tuaregs, nothing has been resolved.

On the other hand, France (and international actors) is as active as ever in trying to hold on to Mali’s colonial situation – financially and with military “aid”. The purpose of the meeting organized by the African Union (AU) at the end of its 20th Summit of Heads of State and Government was to mobilize funds to finance the operations of the International Support Mission in Mali (MISMA) as well as to strengthen the capacity of the Malian army. Initially, with the support of the EU, the AU will provide $461.5 million for the operations of the International Support Mission in Mali.

Conclusions

Turning back to Mali, let us summarize why ECOWAS is so actively trying to maintain at least the appearance of a sustainable political regime. The stability of the entire region depends on the situation in Mali in the event of destabilization – in the eyes of ECOWAS officials, with regular escalations, first, foreign investors will be afraid to invest in the region’s economy, and secondly, the patience of Western officials is running out (including with regard to the currency “eco”, the introduction of which has been postponed for the second time).

The situation in Mali is extremely difficult, and foreign loans and new currencies do not solve conflicts with local militias and jihadists, as well as protests of various opposition – from influential preachers (like Mohamed Dicko) and singers (like Salif Keita) to left-wing activists and militant tribal representatives. The general fatigue of all these groups leads to the conclusion that local agreements without elites and French participation are more possible than “international consensus”. And certainly, ECOWAS, which has proven to be ineffective, is unable to reconcile the complex political and religious palette of Mali’s inhabitants.

Leave a Reply